It’s production time at my school, so the posting has slowed down a little bit in the last week or so. Normal service will be resumed next week. However, one little item that made me smile was an article two days ago in The New York Times by Dave Itzkoff, entitled The Only Certainty Is That He Won’t Show Up which is about the right way to say ‘Godot’. The reason why this resonated was that a touring production of Waiting for Godot came through Hong Kong earlier in the year, during a holiday when I was away, and some of my students went along to see it. When school was back in session, and they were eager to share their experiences and thoughts, many of them were pronouncing it god-OH, stressing the final syllable, rather than the first. I chose not to put them right (so I thought) as I was delighted they had gone to see one of the theatre classics under their own steam.

Here’s the article I mentioned above.

The Only Certainty Is That He Won’t Show Up

The Right Way to Say ‘Godot’

Maybe Godot never appears because everyone is mispronouncing his name.

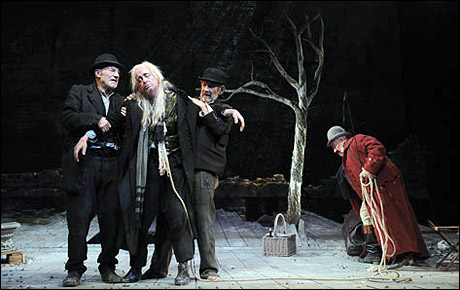

More than 60 years after the debut of“Waiting for Godot,” Beckett’s absurdist drama about two vagabonds anticipating a mysterious savior, there is much disagreement among directors, actors, critics and scholars on how the name of that elusive title figure should be spoken.

“GOD-oh,” with the accent on the first syllable, is how “it should be pronounced,” said Sean Mathias, the British director of the latest a Broadway revival of “Waiting for Godot,” opening later this month at the Cort Theater.

“It has to be, really,” he said. “There’s no other way to do it.”

But the theater critic John Lahr said that rendering “is too obvious” for the playwright Samuel Beckett, with its suggestion of the Almighty.

“Beckett is more elusive and poetic, and he wouldn’t hit it on the head like that,” said Mr. Lahr, a longtime contributor to The New Yorker, who instead advocates for “god-OH,” with the accent on the second syllable.

Georges Borchardt, a literary agent who represented Beckett and continues to represent his literary estate, suggested even a third pronunciation was possible.

“I myself have always pronounced it the French way, with equal emphasis on both syllables,” Mr. Borchardt said in an email.

Mr. Borchardt said he had consulted with Edward Beckett, a nephew of the author, who told him that his uncle pronounced it the same way, and that Edward Beckett could not see “why there should be a correct or incorrect way of pronouncing Godot.”

“As the agents for the estate,” Mr. Borchardt continued, “we do not insist on any particular pronunciation.”

There seems to be nothing to be done to reconcile these competing camps, and productions of “Godot” do what they will. In a video recording, Peter Hall, who directed the first British production, in 1955, pronounces it GOD-oh. An American television production from 1961 starring Burgess Meredith and Zero Mostel uses “god-OH.” Discussing his role in the 2009 Broadway production, Nathan Lane says “GOD-oh.”

“I don’t think there is a mathematical solution to this problem,” said Mark Nixon, the director of the Beckett International Foundation at the University of Reading in England. Dr. Nixon said he believed the name was correctly pronounced with a stressed first syllable. But, he said, “I don’t feel strongly in the sense that I would correct somebody who said it differently.” Still, he did not dismiss the Godot question as a trivial issue. “Nothing’s trivial when it comes to Beckett,” he said.

The debate would surely please Beckett, an Irish author who originally wrote “Waiting for Godot” in French before translating it into English, and whose work embraced ambiguity and resisted easy interpretation. As this Nobel laureate wrote, “no symbols where none intended,” but he kept his intentions mysterious and seemed to leave symbols everywhere. The pronunciation of Godot, like the name itself, seems pregnant with meaning, yet ambiguous.

One might think that Beckett’s own writing would plainly reveal his wishes, but, gosh, no.

According to “The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett” (Grove Press), when “Waiting for Godot” was performed in the 1980s by the San Quentin Drama Workshop, Beckett sought “to counter the natural American tendency to stress the second syllable” and asked his actors “consciously to pronounce it with the stress on the first syllable instead.”

Dr. Nixon said that recordings of the author’s voice are extremely rare — “only about four, or four and a half, are in existence.”

“I’ve heard all of them,” Dr. Nixon said, “and on none of those recordings does he use the word Godot. So, unfortunately, that’s not a route we can take.”

The French-looking name Godot may seem to call for a French pronunciation. But in an English-language production, speaking Godot without stressing either syllable “would be similar to saying ‘Paree’ for Paris,” explained the actor Adrian Dunbar, an experienced Beckett performer.

“Although not incorrect,” he said, “it does sound a little, shall we say, faux.”

There is no definitive origin story for the name Godot, either. It may be Beckett’s reference to the French bicyclist Roger Godeau or to French slang words for boots, a pair of which feature prominently in the play.

Mr. Lahr rejected the interpretation that Godot was simply a stand-in for God, an idea he said was too easily conjured up by the pronunciation GOD-oh.

When his father, the actor Bert Lahr, played Estragon in the original American productions of “Waiting for Godot,” Mr. Lahr said “god-OH” was used.

“It keeps it open-ended and more painful, almost, as if there’s nothing out there,” Mr. Lahr said. “Which there isn’t, in Beckett’s vision.”

And for American ears, the GOD-oh pronunciation can sound affected, and can take some getting used to.

Mr. Mathias, whose production of “Waiting for Godot” was originally staged in the West End of London, said that when it transferred to New York, “we had to train everybody” to embrace this pronunciation.

“Could you imagine the poor crew?” Mr. Mathias asked cheekily. “Anybody who says ‘god-OH,’ I say, ‘Excuse me? What’s that? We’re not doing that play.’ Poor things.”

Shane Baker, who translated “Waiting for Godot” into Yiddish, said that actors in this version of the play said “god-OH” because “that’s how it’s known in America.”

“I was the translator,” said Mr. Baker, who also played Vladimir in the New Yiddish Rep production at the Castillo Theater in Manhattan. “But the producer and director wanted god-OH, so there you have it.”

“We did it wrong,” he said. “Look, I had other battles I had to fight.”

Mr. Baker added that, over the years, “Waiting for Godot” had become part of “the people’s imagination.” It has been paid tribute in films like “Waiting for Guffman,” and the subject of a “Sesame Street” parody, “Waiting for Elmo.”

Saying “god-OH,” he said, has become part of the vernacular, and it is too late to talk audiences out of it.

“The rest of the play is jarring enough,” Mr. Baker said. “Why upset them?”

A bit of a silly post today. Theatre is full is superstitions and actors are said to be equally full of superstition. I have been doing a little bit of a trawl through these, prompted by a new series being published in the UK Guardian, My dressing room, where actors are interviewed – not surprisingly – in their dressing rooms. What struck me as I read them, is that they all have their rituals, totems or preparations (read superstitions) that go with them wherever they are performing.

A bit of a silly post today. Theatre is full is superstitions and actors are said to be equally full of superstition. I have been doing a little bit of a trawl through these, prompted by a new series being published in the UK Guardian, My dressing room, where actors are interviewed – not surprisingly – in their dressing rooms. What struck me as I read them, is that they all have their rituals, totems or preparations (read superstitions) that go with them wherever they are performing.

Of course one of the other most famous theatrical superstitions is not saying the word ‘Macbeth’ inside a theatre, but referring to it as The Scottish Play. Theatrical folklore has it that, as revenge for Shakespeare’s inclusion of a number of accurate spells within the play, a coven of witches cursed it for all eternity. Whether or not you believe this explanation is irrelevant, though, because the ill-fortune associated with the play is backed up by many examples over its four hundred year history. Initially, King James banned the play for five years because he had such a dislike for it, but there are also more bloody examples: there was an unpleasant and lethal riot after one showing in 19th century New York and one Lady Macbeth fell off the front of the stage while sleepwalking, dropping nearly twenty feet. Even Lawrence Olivier wasn’t free from the curse, as one of his performances was enlivened by a falling stage weight which landed only inches from him mid-performance. Having said this, I quite like the more prosaic options – that there is more swordplay in it than most other Shakespeare plays and, therefore, more chances for someone to get injured – or, and the one I believe most likely is that, due to the plays popularity, it was often run by theatres that were in debt and as a last attempt to increase audience numbers; the theatres normally went bankrupt soon after.

Of course one of the other most famous theatrical superstitions is not saying the word ‘Macbeth’ inside a theatre, but referring to it as The Scottish Play. Theatrical folklore has it that, as revenge for Shakespeare’s inclusion of a number of accurate spells within the play, a coven of witches cursed it for all eternity. Whether or not you believe this explanation is irrelevant, though, because the ill-fortune associated with the play is backed up by many examples over its four hundred year history. Initially, King James banned the play for five years because he had such a dislike for it, but there are also more bloody examples: there was an unpleasant and lethal riot after one showing in 19th century New York and one Lady Macbeth fell off the front of the stage while sleepwalking, dropping nearly twenty feet. Even Lawrence Olivier wasn’t free from the curse, as one of his performances was enlivened by a falling stage weight which landed only inches from him mid-performance. Having said this, I quite like the more prosaic options – that there is more swordplay in it than most other Shakespeare plays and, therefore, more chances for someone to get injured – or, and the one I believe most likely is that, due to the plays popularity, it was often run by theatres that were in debt and as a last attempt to increase audience numbers; the theatres normally went bankrupt soon after.