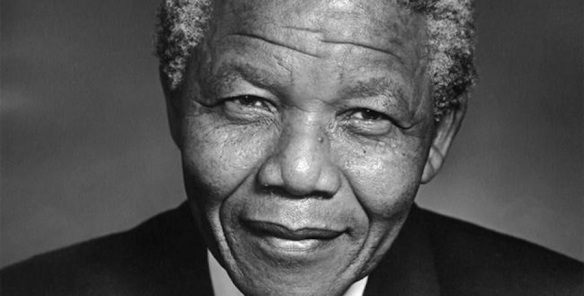

The death of Nelson Mandela two days ago has, quite rightly, brought about a slew of obituaries, articles and opinion pieces from around the world. One particularly caught my attention, written by Emily Mann for the LA Times. It talks about the great man’s unwitting, yet powerful effect on theatre. I’m posting it today simply as a tribute, but is worthy of a read and I whole heartedly suggest that the plays Mann talks about are worth a read too.

I especially recommend Athol Fugard’s The Island and Sizwe Bansi Is Dead (which was also written by Fugard in collaboration with Winston Ntshona and John Kani). The former is set in an unnamed prison, clearly based on South Africa’s notorious Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela was held for twenty-seven years. It focuses on two cellmates, one whose successful appeal means that his release draws near and one who must remain in prison for many years to come. The latter is a beautiful elegy about the loss of identity and how oppression can make desperate people do desperate things. The play’s protagonist, Sizwe Banzi, is forced to steal the identity papers, and thus the identity, of a dead man in order to get work in apartheid era South Africa.

Nelson Mandela dies: His legacy to the arts

Many people know that Nelson Mandela’s life inspired novels, poems, plays and films, but few people know how powerful his effect on the theater was and how powerful the theater’s effect was on him.

The theater served as a mirror to Mandela, each side influencing and reflecting the other, placing them both in time.

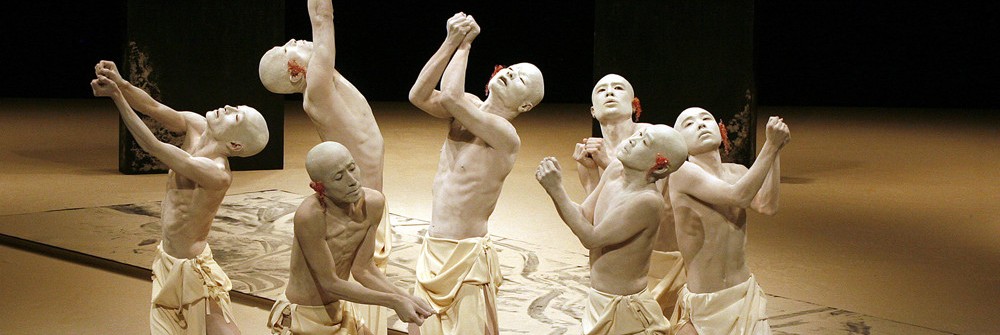

At the height of the apartheid era, the Market Theater in Johannesburg and the Space Theatre in Cape Town, both defiantly nonracial venues in a racially divided country, produced shattering plays about black life under the apartheid regime.

These plays premiered in South Africa in the 1970s and ’80s and then flooded onto the world stages. The plays triggered global outrage at the South African government and support for the struggle for freedom Mandela represented.

Athol Fugard’s “The Island” and “Sizwe Bansi Is Dead” (co-created with actors Winston Ntshona and John Kani) and “Master Harold and the Boys”; Percy Mtwa, Barney Simon and Mbongeni Ngema’s “Woza Albert”; and Ngema’s “Sarafina” along with many other plays of staggering power sparked a conflagration of local and international protest and helped Mandela bring down the apartheid government.

As Fugard once said to me and others, “I sometimes have to subscribe to the old cliché that the pen is mightier than the sword. It certainly was true in this case.”

Mandela’s arts legacy reaches beyond the apartheid era. He continued to inspire theater makers around the world to write those plays that would expose social injustice.

One of my plays, “Greensboro, a Requiem,” is about the Ku Klux Klan massacre of a multiracial group of anti-Klan demonstrators in Greensboro, N.C., in 1978. It brought national attention to the event and to the shocking acquittals of the Klan by an all-white jury.

In its wake, the play inspired the mayor and the city of Greensboro to convene America’s first Truth and Reconciliation Commission, modeled on Mandela and the Rev. Desmond Tutu’s commission in South Africa.

The citizens of Greensboro, as in South Africa, chose to face painful truths about their past so they could enter a future together with a mutually agreed-upon history and a new understanding of each other’s lives. This, too, is Mandela’s legacy. A play can inspire social change.

During Mandela’s long life on the world stage, his influence has been multifaceted and his reach long. His profound contribution to the arts, both the work influenced by him and for him, made not only world but theater history, and his legacy continues to inspire those who work in the theater for social justice.

Pingback: Literary Redundancy – Not A Chance | Theatre Room Asia