In July I wrote a post, Body Talk, which dealt with how theatre has been used around the world by the global movement to end violence against women and girls. It’s focus was Eve Ensler’s play, The Vagina Monologues, and a play touring in China, Our Vaginas, Ourselves. A week or so ago, The Atlantic published an article by Gabrielle Jaffee which takes the debate back to China:

Performing The Vagina Monologues in China

The ongoing controversy of the iconic play reflects feminism’s struggle to establish a toehold in a still conservative society.

“When I first heard about The Vagina Monologues, I was shocked. I thought, how could someone give a play a name like that?” says Xiao Hang. That was five years ago, when Xiao Hang was, by her own admission, “mainstream and quite conservative.” But after volunteering for an NGO in her sophomore year at college, she began to see society through a different lens. She no longer thinks, as she once did, that “it isn’t elegant to talk about your vagina in public.” In fact, she thinks it’s vital to.

Today Xiao Hang is one of the organizers behind Bcome, the Beijing-based feminist group which has put on around a dozen performances of The Monologues this year to mark the ten-year anniversary of its first showing in China. Performed in over 150 countries worldwide in some 50 different languages, Eve Ensler’s play was first shown in the Mainland at Guangzhou’s Sun Yatsen University in 2003.

In their offices just outside Beijing’s third ring road, Xiao Hang and Bcome’s other volunteers are preparing leaflets to send out for the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. The leaflets have titles such as “20 Misconceptions about Sexual Violence,” “The ABCs of Feminism,” and “Resist Verbal Abuse.”

“We’ve already done lots of online and print promotions as well as panel discussions. The Vagina Monologues is new, fresh and attention-grabbing,” says Ai Ke, another organizer. “It’s not just a play, it’s a tool for spreading feminism, a method for public education.”

To prepare the script, the organizers translated from the English version, took parts from past Mandarin versions, and created original scenes through a series of workshops they ran last year. At the beginning of each workshop, they voted on which topic they wanted to discuss (“We’re very democratic,” laughs Xiao Hang), noted down their own experiences, and gave key words to the scriptwriters. “We wanted to localize the play as much as possible, so we added issues such as the obsession and anxiety over virginity,” explains Ai Ke.

With their script complete, Bcome’s committee organized shows at Beijing’s LGBT center, at culture cafes, and at an art space where they performed to an audience of 400. They also put on the play for a community of migrant sex workers (“This helped us better understand them and write a scene about their lives”) and organized college campus productions—including a now notorious rendition by female students at Beijing Foreign Studies University (BFSU).

The BFSU students caused an internet storm earlier this month when, in an effort to promote their version of the Monologues, they posted pictures of themselves holding up messages from their vaginas to the popular social network RenRen. Written in English, Chinese and Korean, the messages ranged from “My vagina says: I want freedom” and “My vagina says: I want respect” to “My vagina says: You need to be invited to get in.” The images were soon reposted on Sina Weibo and picked up by local media outlets, who focused on the girl’s “confessions.” A video of the images received over 2 million views on Sina.

The wave of online misogyny that followed was nasty. Commenters focused on the women’s looks (“Seeing their faces, I’ve lost all interests in their vaginas” said one @Taoist_Mua), others expressed shock that students at one of the country’s top universities could have written such things (“How could BFSU admit such vulgar girls?” @冬天的亭子) or simply resorted to pure name-calling (“These ignorant grandstanding tarts” @保护地球绿色家园). One user, @shendeon, even exclaimed, “If my daughter did this, I’d slap her across the face.”

***

These reactions only seemed to validate the need for performances of The Vagina Monologues in China. The critics “have this image that female university students must be pure,” says Xiao Hang. “They were terrified because women in China never talk about sex in public.”

Bcome received mostly positive feedback for their other performances of The Vagina Monologues, which included a traditional xiangsheng (comic dialogue) about different kinds of moaning when reaching a climax and an interactive section where audience members were invited to share their stories. “Some people laughed, some people were so moved that they cried,” says Ai Ke. Several people came up to her afterwards and thanked her for the “growing experience” they had, or for convincing them that they were not “odd” for thinking about such things.

However, Ai Ke admits that the people who came to watch the play were probably already open-minded. In China, this isn’t surprising: There’s a difference between intellectual elites performing in the safe environment of the student union or culture cafes and the opinions of the public at large, which the BFSU students were exposed to online.

Chinese government repression plays a key role, too. While the last decade has seen The Vagina Monologues performed many times at universities across the country, a professional production in Shanghai was banned in 2004 after hundreds of tickets had been sold and a 2009 production was forced to call the show “The V Monologues” instead of the full name. Bcome found that “as soon as the word vagina was mentioned,” official theaters and even some small independent outfits such as Beijing’s Peng Hao and Mu Ma theaters refused them.

The Monologues’s checkered history in China reflects the inconsistent approach towards sex and sexuality in the country. While the government continues to crack down on pornography and vulgarity, reform and opening of the last few decades has coincided with more liberal attitudes towards sex. Indeed, in China, sexuality is on view everywhere: Even state-run news outlets like Xinhua and the People’s Daily use soft porn slide-shows to bump up click rates.

But just because there’s more flesh on view than during the puritan past, that doesn’t necessarily women’s sexual rights have improved. Using the “v-word” is still a taboo in China. “China is still a male dominated world,” says Ai Ke. “The sexual freedom gained in the last few years has been for men. The pleasure that women can get from sex is so seldom talked about.”

And it’s not just the female right to enjoy sex that has become an important feminist issue in China: There’s also the right to protect their bodies. Around a quarter of China’s female population suffers from domestic abuse, according to the All-China Women’s Federation, but there is no law specifically targeting the crime.

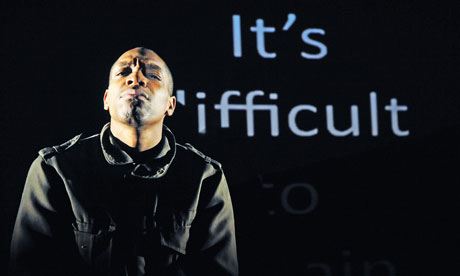

Women are beginning to speak out. Last year, after the official Sina Weibo account of the Shanghai Subway Line 2 posted a photo of a passenger in a revealing dress with the caption “dressed like that, it’s no wonder you get harassed. There are many perverts on the subway, can’t catch them all. Girl, have some self-respect!” many net users were outraged. For their part, Bcome organized flash mob readings of the Monologues scene “My Short Skirt” on the Beijing subway. [click the image below for video the performance].

“Most people just looked awkward, tried to not to look us in the eyes and instead fiddled with their phones,” admits Xiao Hang. Perhaps asking people to face sexual issues directly remains too much to ask for in China.

More reassuring, though, is what happened after each of their performances. When the women approached passengers with a petition to support legislating against domestic violence, they collected over 10,000 signatures in 15 hours. That, at least, is something to celebrate.