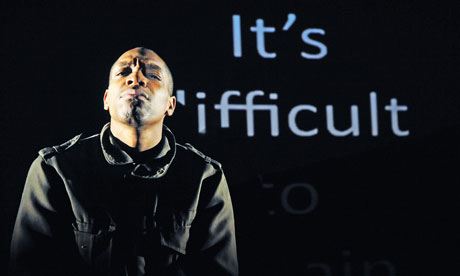

One of the smash hits on the London stage at the moment is Coriolanus. It is one of Shakespeare’s more violent plays with big, bloody battle scenes, riots on the streets of Rome and battles on the Senate floor. This current production, starring Tom Hiddleston has been roundly applauded.

Obviously one of the things that this production does well is violence and death, most spectacularly, it would appear, Coriolanus’ own death. Given my comments recently in my post, Dying On Stage, I was intrigued to read an interview with Richard Ryan, the fight director on the show, who was talking to Frances Wasem in The Telegraph. In it, Ryan talks about how he approached the job:

How to choreograph a theatrical fight scene

’ve worked for 20 years in theatre and film as a fight instructor and stunt coordinator, but I trained as an actor, so in many way, working in theatre always feels like coming home. My part in the production is to create an exciting fight, which has energy and pace, develops the characters and the plot – and to do it all safely.

The fight director is involved from the very beginning of a production. Wherever possible I like to sit in on rehearsals to get a better sense of the world the director is trying to create. For Coriolanus, Josie (Rourke, the director) outlined the contemporary feel of the play and talked about the Roman look. We had to merge those two elements in the fight scenes. The director will tell me if they envisage a more visceral, hard-hitting or a swashbuckling-style fight. We’ll also discuss any specific plot elements that they wish to include. In Coriolanus it was important to establish Coriolanus as a warrior and Tullus Aufidius as a worthy adversary.

Research is part of how a fight is put together. I might visit museums to look at how a warrior, at that time, would have fought and moved. For Coriolanus, I looked over illustrations of Roman tactics and battles and discussed with Lucy (Osborne, the costume designer) a need for a range of movements (so that skin doesn’t chafe). We make sure the metal of the stage armour is lighter than real armour and the sword blades are made of aluminum, not steel. They would still cause damage if they came into contact with the body, though. We were lucky that Lucy got us the boots early on in rehearsals, as their weight and grip changed the type of choreography.

I also talk to the set designer and lighting technician. Principally, I need to ensure that the actors can move around the stage, can see each other’s movements, and that they won’t slip or fall. The actors need to be able see the swords as they fight. Losing sight of the blade in a beautiful sidelight is dangerous. I’ll ask for areas of the stage, which see heavy fighting, to be reinforced. The safety of the actors is crucial, everything from the type of floor to the consistency of stage blood is thought about (in case the actors slip). If a piece of furniture is going to be slammed into, then you reinforce that particular bit of the set, so no one is hurt.

One can talk a good fight, but it’s in the doing that all the work happens. After discussion with Josie and armed with an idea of costumes and weapons, the next step is to start choreographing – and to put the fight on its feet.

I sketch out on paper what I think the floor pattern of the fight will look like, but that’s just for myself. The fight is crafted in the rehearsal room, with and on the actors. The actors might be left or right-handed or have an old injury that makes them hesitant. I base the fight on the story and what the actors can do. Their involvement is key. I need to create a fight scene that is exciting, but that’s also sustainable for the actors to perform eight times a week.

In rehearsals, safety is very important. I’m a fencing coach and black belt martial artist so I’m aware of potential injury. There are crash pads at the back of the room, for when an actor is thrown. I also have back pads, knee and elbow pads. In one fight, both Hadley Fraser and Tom Hiddleston are thrown as they grapple and the crash mat was used as they learned and became familiar with the mechanics of the throw.

So that swords don’t actually hit the actors we use a technique called “off-line”. The sword basically makes contact with the area that an actor was previously in. The actors continually watch for spaces to move into. There’s a structure to a fight, which is like a dance; the moves are done over and over until they are second nature. In early rehearsals you see an actor counting out the moves (one, two, three…), but by the time the show opens, they’re invisible.

Ensuring that the actor is able to convey their character in a fight scene is fundamental to my brief. In Coriolanus I need to establish Coriolanus as a warrior and Tullus Aufidius as a worthy adversary. We also need to confirm Tom as a leader, which is achieved through a combination of what he does, the way others respond to him and using stagecraft to ensure he is in strongest position on stage.

In the action, similar principles apply. Tom (Coriolanus) has minimal, but definite movements, whereas junior warriors would quite simply move more. We’d contrast a confident stillness for Tom, with a more edgy, nervous physicality of a less experienced soldier. Tom and I tried to develop an icon fight style, reflective of his vision for Coriolanus. We settled on a signature low stance, from which he launches into explosive attacks.

The energy of a fight scene should build. You do this by creating the illusion that the fight is picking up pace. You start the fight with the actors doing bigger moves – and reduce them in size as the fight gets more intense. You also reduce the number of pauses in the action, as anger builds. It gives the illusion that the moves are faster and more violent, that tempers have frayed. But it’s an illusion; the reality is it’s very controlled.

I had the good fortune to teach Tom swordplay at RADA. Then, as now, he was diligent, enthusiastic and physically fit. He also contributed ideas – and did so on Coriolanus too. Tom and I had been debating whether to “play” an injury, after he was thrown. I wasn’t convinced it would work. So, in a run through of the fight – with the rest of the cast present, who hadn’t been privy to our conversation – Tom landed from the throw and faked the injury. It worked wonderfully and the rest of the cast liked it, so I conceded that Tom was right. Tom had a broad grin for the rest of the day.

Not surprisingly this set me off on a research trail and I was quite astonished by what I found – mountains of information, societies, guilds, guides, schools and even lesson plans about stage combat. One article from Armour Archive deals specifically with sword fighting, Stage Combat 101. Meron Langsner, himself a fight director offers loads of links to all things violent on stage. Brigham Young University Theatre Education Database offers four lessons and associated resources, including a great little Terms and Definitions document.

Then there are instructional videos like this one from Armstrong Atlantic State University Drama Professor, Pam Sears, revealing the tricks to the illusions of combat in theatre.

.

I also came across the interview from Stage Source in which four practitioners, Angie Jepson, Robert Najarian, Ted Hewlettstage and Meron Langsner talk about stage combat, fight choreography, and something called Violence Design which seems to be a relatively new term that covers everything violent on stage. It is 45 minutes long, but very interesting – click the icon below to listen

There are professional bodies, such as the Society of American Fight Directors and The British Academy of Dramatic Combat who train actors and certificate teachers. There are people who blog about stage combat, my favourite being I’m So Not Going To Hit You. There are even Facebook groups, such as Girls Fight, which is set up to promote women in stage combat, of which there are few. It seems to be a male dominated profession. Having said that, there is a great little interview here with Alison de Burgh, who was the first ever professional female fight director in the UK.

What I started to glean on my quick tour around stage combat was that much of the training has its basis, not surprisingly, in the kind of discipline that comes with martial arts. This article and programme recording from NPR, In Japan, ‘Sliced Up Actors’ Are A Dying Breed, is about a Japanese actor, Seizo Fukumoto, who has been killed more than 50,000 in his career. Although largely on film, Fukumoto, is known as a Kirareyaku, which roughly translates as ‘chopped up actors’. His art is known in Japanese as tate, a stylized sort of stage combat that combines elements of martial arts, dance and kabuki theatre. You can listen to the programme by clicking this icon:

What I started to glean on my quick tour around stage combat was that much of the training has its basis, not surprisingly, in the kind of discipline that comes with martial arts. This article and programme recording from NPR, In Japan, ‘Sliced Up Actors’ Are A Dying Breed, is about a Japanese actor, Seizo Fukumoto, who has been killed more than 50,000 in his career. Although largely on film, Fukumoto, is known as a Kirareyaku, which roughly translates as ‘chopped up actors’. His art is known in Japanese as tate, a stylized sort of stage combat that combines elements of martial arts, dance and kabuki theatre. You can listen to the programme by clicking this icon:

What is clear, and I always knew this of course, is that stage combat is highly skilled and potentially very dangerous if you are not trained properly. There is a scary list of when things have gone wrong here. So as we say in an increasingly litigious world, Don’t try this at home, kids!