A square-headed figure stands in a jagged harlequin costume, like a toddler’s drawing of a Christmas tree, beside a red-clothed character with black spines emerging from his limbs. There is a portly green-skinned man bursting out of a tight red vest, while another figure’s body swells from a triangular skirt in a big blue bulge.

Set against a mysterious monochrome backdrop of triangles and squares, these were the costume designs of then little-known Kazimir Malevich for the world’s first “futurist opera,” Victory Over the Sun, produced in St Petersburg in 1913. Complete with a libretto in the experimental “zaum” language – a kind of primeval Slavic mother-tongue, mixed with birdsong and cosmic utterances – it infuriated audiences, who reacted with violent outrage.

Malevich was not deterred. The stage sets formed the basis for his first Black Square painting, and the foundations for his fractured visual language of suprematism, one of the defining movements of the period. It was here in these gnomic theatre designs that he began his urgent pursuit of the “supremacy of pure artistic feeling”, of geometric splinters flying through limitless space, fuelled by the impending trauma of revolution.

These striking drawings form the opening to a new free exhibition in the V&A’s theatre and performance galleries, which traces the effect of war and revolution on Russian avant-garde theatre design, from 1913–33, a period that saw an earthquake of artistic transformation.

Comprising 160 works by 45 designers, much of what’s on show has been unearthed from the dusty depths of the Bakhrushin Theatre Museum archive in Moscow, some exhibited in public here in London for the first time – and it is a thrilling hoard.

Lyubov Popova’s fantastic mechanical set for The Magnanimous Cuckold, 1922.

Facing off against Malevich are the early costume designs of Vladimir Tatlin, who would go on to dream up the spiralling skeleton of the Monument to the Third International, a plan for a gargantuan double-helix structure that would have loomed 400m above St Petersburg. While Malevich was brewing up a universe of dynamic shards, Tatlin’s designs – for operas with nostalgic titles such as Life for the Tsar and His Disobedient Son Adolf – reveal the beginnings of his constructivist style.

These counterpoints set the tone for a show that reveals the breadth of artistic styles spawned in these tumultuous years, with the theatre proving a hotbed of experimentation and a powerful vehicle of revolutionary propaganda.Women designers loom large, with the dazzling work of Alexandra Exterfeaturing extensively, from her bold reinventions of classics like Romeo and Juliet, to impossibly futuristic costumes for Aelita, one of the first ever sci-fi films, made in 1924. Based on a Tolstoy novel, it tells the story of an engineer who travels to Mars, falls in love with the Queen of the Martians, and organises a revolution. The space-queen was conceived as a Soviet Barbarella, clothed in a swirling dress of orbiting loops, topped with a many-pronged head-dress that gives her the look of a human TV aerial. It exudes the excitement of what the promised revolution would bring, the humble engineer discovering a brave new world through hard work. Utterly groundbreaking for its time, Exter’s alien set designs would go on to inform the dreamy aesthetic of Flash Gordon and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis.

Vladimir Tatlin, costume design for Life for the Tsar, 1913-15.

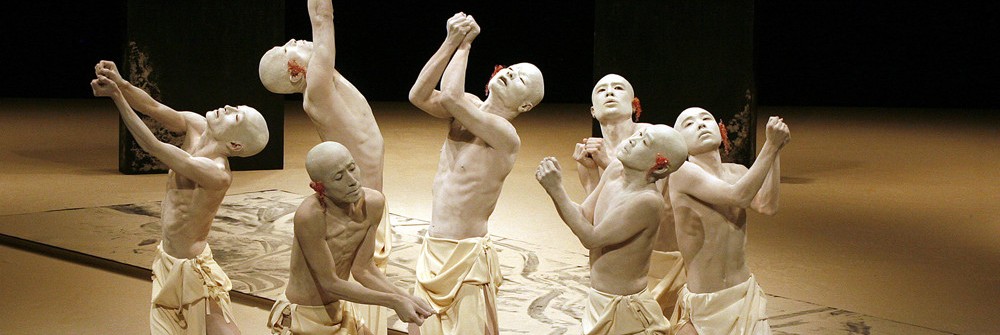

“I want to burn with the spirit of the times,” declared Vsevolod Meyerhold, another influential figure of the period, and one of most enthusiastic activists of the new Soviet theatre. He joined the Bolshevik party in 1918 and became an official of the theatre division of the Commissariat of Education and Enlightenment, trying to radicalise Russian theatres under Bolshevik control. Developing what he called “biomechanics”, he championed a form of acting in which bodily expression was all, teaching his students gymnastics and circus skills, in a bid to transform the theatre from a place of naturalism and emotion to a full-blown fairground spectacle.

“Meyerhold laid the foundations for modern physical theatre, and groups like Complicite,” says curator Kate Bailey, “as well as a lot of the techniques of projection and moving sets that we take for granted as part of contemporary theatre design.”

The Queen of the Martians, costume design by Alexandra Exter for the 1924 sci-fi film Aelita, based on a Tolstoy novel

A key to realising his vision was Lyubov Popova, the daughter of a textile merchant who had been a member of Malevich’s Supremus art group from 1914-16. She produced a spectacular moving set for his production of The Magnanimous Cuckold in 1922, a model of which takes pride of place in the exhibition. The play follows the trials of a miller who suspects his wife of being unfaithful and pursues her lovers through the village, and Popova transforms the mill into an all-consuming acting machine, a thrilling landscape of rotating cogs and wheels.

Under the influence of Meyerhold, theatrical characters were reduced to types, emotion and psychological experience substituted for the gawp of physical and mechanical prowess. Similar narratives recur, in which “impure” characters of merchants and royalty, capitalists and priesthood, face off against “pure” peasants and sailors, the old order trounced by the newly awoken masses. Costumes of the old world are heavy and clumsy, set against the thrusting, cubo-futurist lines of the new Communist utopia.

It all comes to a satirical climax in Vladimir Mayakovsky’s comedy, The Bedbug, in which the brave Bolshevik protagonist, Prisypkin, is cryogenically frozen in an impossibly modern-looking spacesuit – to designs by Alexander Rodchenko – to be thawed when the ideal Communist world has been attained in 1979. Severely underwhelmed when he awakes, he finds a bedbug on his body, which becomes his only friend.

Alexander Rodchenko costume design for Bedbug, 1929, a comedy by Mayakovsky whose hero is frozen for 50 years to await a Communist paradise

It is an appropriately gloomy end to the exhibition, which concludes with the rise of Stalin, who presided over a return to socialist realism, and the accompanying vicious backlash against the avant-garde. The final piece on show is a miraculous wooden and plaster model for Mayakovsky’s satirical play, Mystery-Bouffe, directed by Meyerhold, which depicts the North Pole, where the earth’s last survivors have voyaged, to be offered the choice between heaven and hell. They decline heaven, in favour of the promised land of the Communist paradise.

It was not to be so for the two leaders of the avant garde under Stalin: disillusioned and driven to despair, Mayakovsky shot himself, while Meyerhold was arrested, tortured and executed. “Theatre is not a mirror, but a magnifying glass,” Mayakovsky once said. And their powerful lens clearly looked a little too closely for the regime’s comfort.

This year I am teaching two new courses, both of which lay a greater emphasis on student understanding of the theatre production processes than I have previously had to teach. The roles of performer, director and collaborator have always been at the heart of my classroom, with design at the periphery. However, for me personally as a theatre-maker, I have always enjoyed the creative process of theatre design and the challenge of bringing a sense of place, time, theme and atmosphere to life for an audience. I wanted to find a way of teaching the art of the designer – lighting, costume and set – that explained the fundamentals without drowning my students in unnecessary theory. Take a look at any published text on stage lighting and you will know what I mean. So I set off on a journey that was fascinating and hugely informative and today’s post is to share some of what I have found.

This year I am teaching two new courses, both of which lay a greater emphasis on student understanding of the theatre production processes than I have previously had to teach. The roles of performer, director and collaborator have always been at the heart of my classroom, with design at the periphery. However, for me personally as a theatre-maker, I have always enjoyed the creative process of theatre design and the challenge of bringing a sense of place, time, theme and atmosphere to life for an audience. I wanted to find a way of teaching the art of the designer – lighting, costume and set – that explained the fundamentals without drowning my students in unnecessary theory. Take a look at any published text on stage lighting and you will know what I mean. So I set off on a journey that was fascinating and hugely informative and today’s post is to share some of what I have found.