By way of post script to my last post about the restaging of Miss Saigon in London, I want to share some of the reviews. Before that, however, a great piece by Mark Lawson in The Guardian that caught my eye. In Miss Saigon, Yellow Face and the colourful evolution of answer plays Lawson talks about the David Henry Hwang’s new play, Yellow Face which opens with a character talking about his role in a campaign against the casting of Jonathan Pryce as the Asian character of The Engineer in Miss Saigon’s original Broadway production. Hwang is probably the most famous Chinese (American) english language playwright of our time and much of his work reflects his heritage.

There’s a phenomenon in pop music of the “answer song”, written in direct response to another track: Carole King, for instance, recorded a number called Oh, Neil! after hearing Neil Sedaka’s Oh, Carol! There’s a similar – though sparser – theatrical genre of answer plays and a recent example is currently running at the National Theatre: Yellow Face by the Chinese-American dramatist David Henry Hwang.

Hwang’s play begins with a dramatist called DHH describing the events that followed his involvement in a campaign against the casting of Jonathan Pryce as the Asian character of The Engineer in the 1991 Broadway premiere of Miss Saigon. Timed, presumably not coincidentally, to run at the National just before this week’s opening of the first London revival of Boublil and Schönberg’s musical – with an Asian-American actor, Jon Jon Briones, in the Pryce role – Yellow Face is a response to that show. It is also, in a particularly rare example of a playwright answering himself back, a response to the failure of Hwang’s own 1993 show Face Value, a comedy about racial identity, even though, in Yellow Face, the dramatist exaggerates the content and controversy of that work.

Face Value and Yellow Face, though, were not Hwang’s first involvements with the retorting form. His first hit, M Butterfly (1986), was a tetchy conversation with Puccini’s opera Madame Butterfly, with Hwang using the enduring musical story of an American sailor’s marriage of convenience to a Japanese woman as a parallel to the fact-based scandal of a French diplomat and his Chinese “girlfriend”, who doubly fooled him by concealing the facts of being both a spy and a man.

Curiously, Miss Saigon, which later drove Hwang to his typewriter, was itself inspired by Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, although, for me, the musical belongs to the category of adaptations, rather than answer works. Boublil and Schönberg maintain the basic racial situation of the opera – both the American and Asian central characters are seduced by the dream of the US – while Hwang’s M Butterfly questions cultural stereotypes: challenged on his failure to have spotted the gender of his lover, the French diplomat revealed that he had never really seen “her” body because of typically Asian female modesty. Even so, it is possible, as if in a game of theatrical consequences, to create a chain of five works: Madame Butterfly-M Butterfly-Miss Saigon-Face Value-Yellow Face.

Perhaps, as Miss Saigon came some years after M Butterfly, the writers were influenced, even subliminally, by that other reply to Puccini. But, in any case, the above line of descent suggests that race is often a motivation in response projects. Hwang, from his perspective, queried the European view of the east, while Boublil and Schönberg approached the Vietnam war through their nation’s own history in what the French called Indochine.

Racial redress was specifically the motivation of Arnold Wesker’s The Merchant (1983), in which Shakespeare’s Shylock – and the anti-semitism inspired by him – were given a counter-balancing characterisation by a Jewish writer.

A similar impulse underlies another chain of plays: Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun (1959), Bruce Norris’s Clyborne Park (2010) and Kwame Kwei-Armah’s Beneatha’s Place (2013). Although the connection was more apparent to American than British theatregoers, Norris’s play has a first act (set in 1959) that picks up Hansberry’s characters and narrative of a black family in Chicago and then a second, set 50 years later, that depicts the change in demographics and American race relations. Kwei-Armah was so inflamed by his fellow writer’s treatment of the subject that he wrote his own play, which also has two halves set a half-century apart, but takes a more optimistic view of social progress.

Another string of dramatic inspiration links a British flop and a hit of the late 1950s. As the programme for the recent National Theatre revival of Shelagh Delaney’s 1958 play A Taste of Honey pointed out, the author, at the age of 18, had written her script in angrily rapid response to seeing Variation on a Theme by Terence Rattigan when it was performed in her native Salford. Delaney was irritated by Rattigan’s depiction of gay characters. As it happens, he was gay, while she wasn’t, but he had grown up with cautious attitudes enforced by the legal taboo on male relationships.

Rattigan’s play script was, as the title hints, itself an answer play, inspired by the Dumas drama La Dame aux Camélias. As a result, A Taste of Honey is a variation on a variation on a theme. It would be wrong to say that the three plays hold hands – the second and third are scarcely on speaking terms – but the two English language texts both owe their existence to a precursor.

Less specifically, two of the other most influential plays of the 50s – Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953) and John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger (1956) – can be regarded as answer plays written in response to the prevailing mood of drama at the time, with Beckett questioning the preference for social realism and Osborne objecting to the narrow class range.

In drama – as in pop music – the responses given by these answering works tend to be irritated or argumentative, with Hwang’s M Butterfly, Face Value and now Yellow Face as good examples. The Chinese-American writer was correcting or questioning social attitudes; as, in various ways, were Delaney, Wesker, Norris and Kwei-Armah.

There’s also, though, another type of answer play that gives a friendly or generous response to the predecessor text. David Hare’s South Downs (2011) was commissioned by the Terence Rattigan estate as a sympathetic companion piece for Rattigan’s one-act The Browning Version. And, watching Moses Raine’s amusing and moving drama Donkey Heart at the Old Red Lion theatre, it struck me that his depiction of an English Russian-language student billeted with a family in modern Moscow seemed to include several deliberate echoes of or variations on themes or scenes in Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard: the final scenes of both plays, though different in intent and outcome, feature old Russian men left alone in a family house.

Such critical fancies can often be a result of having seen more plays than most playwrights do and the apparent homages in Donkey Heart might equally be explained by the fact that Russians (Raine’s play was inspired by a visit to the country) behave in a Chekhovian way. Raine was present at the performance I saw and when I asked him afterwards, he confirmed that a production of The Cherry Orchard had been one of his key theatre-going experiences and that the allusion in his conclusion was deliberate.

Human nature being what it is, though, the most appealing answer plays are those that disagree. As artistic director of the Center Stage theatre in Baltimore, Kwame Kwei-Armah staged A Raisin in the Sun, Clybourne Park and Beneatha’s Place last year as a season of dispute. There are no formal joint ticket deals for Yellow Face and Miss Saigon, but anyone who arranges their own double deal will experience an infrequent but powerful form of theatre.

In an accompanying article, David Henry Hwang shares is thoughts on the issue of racial casting – now and then – as well as the role he played in the protests against Pryce’s casting. Racial casting has evolved – and so have my opinions.

Described as a probingly political play by one critic, you can read a review of Yellow Face here. Equally as interesting, from the archive of The New York Times, the 1990 article about the furore surrounding Pryce’s role as The Engineer, which includes Hwang’s original Complaint, Actors’ Equity Attacks Casting of ‘Miss Saigon’.

So now back to the reviews of Miss Saigon, out this week. In extracts from his review for The Guardian, Michael Billington noted:

Seeing the show for the first time in a quarter of a century, I was more struck by its satirical edge than its emotional power. It’s not just that Chris condemns the Vietnam war as “a senseless fight”. Connor’s production implies that, although the story is about a cultural collision, the opposing forces of communism and capitalism carry strange visual echoes.

Ho Chi Minh City, as Saigon became, is embodied by a towering golden statue before which Viet Cong troops parade with well-drilled fervour. America, meanwhile, is symbolised by a Statue of Liberty replica before which chorines dance with military precision. The show is not morally equating the two systems; it is simply suggesting that they feed off each other.

The show’s political point about the casualties of a disastrous war comes across clearly.

Ever the gentleman critic, Billington refuses to get drawn back into the original’s casting debate, preferring to note:

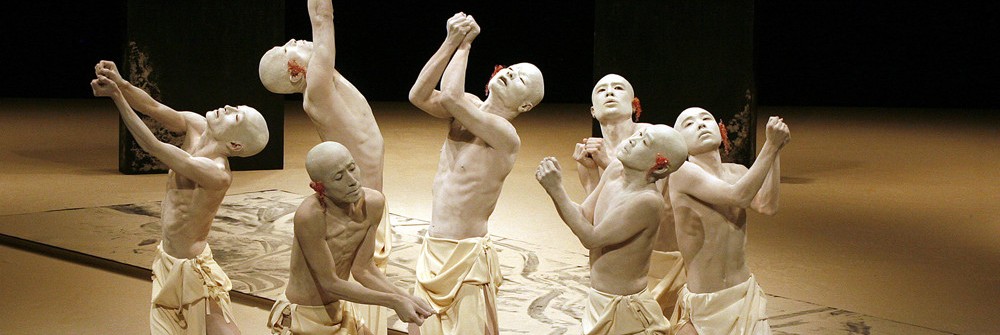

The show’s satirical quality is best embodied by the character of the Engineer: a pimping Pandarus, bred of a Vietnamese woman and a French soldier, he is caught between two worlds and dreams of escape to America.

He was excellently played by Jonathan Pryce in the original, but here Jon Jon Briones makes him an even grubbier, sleazier figure who is the victim of both his background and pathetic fantasies that see him in the penultimate number, The American Dream, pleasuring himself on the bonnet of a Cadillac.

It comes as no surprise really that the other critics have so fair failed to make comment on the context of the narrative, simply bemoaning, like an aged aunt, that the original production was better – Mark Shenton in The Stage and Charles Spenser in The Telegraph to name but two.