In January I wrote a post, No Longer A Refugee, about a group of women refugees who had fled the vicious civil war in their homeland Syria and were involved in the staging of a production of the Greek Tragedy, The Trojan Women. As I was driving to work today I listened to another thought-provoking programme about the project, which was broadcast by the BBC World Service, as part of their Outlook strand. If the January post struck a chord with you, I certainly recommend a listen to the Outlook podcast below:

Category Archives: World Theatre

The High Priestess

February and March is International Arts Festival time in Hong Kong which draws its repertoire from across the globe. One regular visitor every few of years is Pina Bausch’s Tanztheater Wuppertal, who are celebrating their 40th anniversary and this year they will be performing Iphigenia in Tauris which is one Bausch’s earliest works from 1973.

I love this company’s work and alway take myself and my students when they are in town. Prior to their run here they have been performing in London with another piece, 1980. Their appearance in the UK has generated a number of articles that I thought would be worth sharing here. I’ll start with a comment piece by Lyn Gardner for The Guardian which says everything about the genre and why it works for me and my students, who are invariably enraptured by this style of work.

What’s it all about? In theatre, it’s sometimes best if you don’t know

As Tanztheater Wuppertal’s 1980 proves, theatre is at its most potent when it doesn’t offer answers

Somebody once asked the dancer Anna Pavlova what she meant when she was dancing. “If I could tell you that,” she replied, “I wouldn’t dance it.” Theatre’s most thrilling evenings often come cloaked in ambiguity. Too much certainty is embalming in the theatre. It leaves nobody – writer, choreographer, performers, audience – with anything left to discover. I like leaving the theatre feeling as uncertain as when I went in. After all, the world and humanity are too complex and messy to explain easily and tie up in ribbons in a couple of hours.

The performances I most distrust are the ones that tell me emphatically what to think, where the playwright inserts a speech (usually somewhere towards the conclusion so we don’t forget it) that instructs as to what exactly the previous two hours have been about. Sometimes the director does it in an essay in the programme instead. I also distrust those performances that seem simply designed to confirm everything we already know about the world and ourselves. Plays that are “about things” are often really journalism in another guise.

The great Robert Holman once told me that one of the glorious things about writing plays was uncovering in the very act of writing the things that you didn’t know that you knew. With a very good play or an astonishing performance, that can be just as true for the audience too. In the act of listening and watching we suddenly hear a distant chime that reminds us of something we had forgotten or buried; glimpse a ghost version of ourselves; or unexpectedly discover something we didn’t know we knew or felt.

Pina Bausch’s extraordinary and unmissable 1980 – surreal, truthful, mysterious, witty, heart-breaking and painful – is like that. In some ways it is as secretive as an oyster, but it is so emotionally textured and dramaturgically open that the vast stage becomes like a massive mirror of memory, endlessly reflecting our own childhoods, our own griefs and terrifying sense of fragility, and our own ludicrous and absurd way of preening and presenting ourselves to the world in the face of our own mortality. The stage is like the mind itself, sometimes focused and at others surfing wildly. There are interesting things going on all around the edges, as in life. You never quite know where to direct your attention, or where you should look.

The choreographed space between the bodies is as eloquent as the bodies themselves, and the space between stage and audience so fully alive that it invites us to lean forward to hear those chimes and watch those ghosts walk. At the end of three-and-a-half hours, I had no idea at all what it was supposed to mean, but like a frightened child in the dark began to sense and grope towards the light and all the things it meant to me. The show, and the performers, exposed and opened themselves up and invited us to share their uncertainty. In theatre, that’s a rare, brave gift. We should take it when it’s offered.

Also in The Guardian were two other pieces.The first, by Chris Weigand, Performing Pina Bausch’s 1980 – in her dancers’ words, is an interview with three of the performers and the second, ‘She made you feel thrilled to be human’ is by actress Fiona Shaw who saw Bausch’s first London performance.

If you are not familiar with her work (or even if you are) Sanjoy Roy wrote Pina Bausch: clip by clip dance guide for The Guardian, back in 2009, which is definitely worth a read and watch. Some of the original clips referenced in the article have been removed from YouTube, but a little search will find them posted elsewhere on the site.

Sanjoy Roy is a prolific writer an all things dance/dance theatre and his own blog Sanjoy Roy Writing On Dance etc is worth a visit on any number of practitioners. I particularly like his Step By Step Guides to famous and iconic choreographers and companies, and his one on Pina Bausch is a great digest of her work.

Tanztheater Wuppertal tour widely across the globe and I thoroughly recommend you go if they come to a theatre near you.

Being Taken For A Ride

As trends in theatre go, the immersive genre just keeps expanding and redefining itself. This week, some of my own students staged a piece called The Ward which entailed masked audiences, elevators, stairs, four different spaces, touch, taste, smell, specially created video and a cast of 24. It was risky, edgy and played with the form very successfully. We were all delighted with piece and no more so than its creators, deservedly so.

It is seems hardly a week goes by now where I don’t read about a piece of immersive theatre playing somewhere in the world, and this week was no exception. The first I’d like to share is news of a UK company, Rift, who are planning to stage a version of Macbeth. The company have a reputation for staging immersive reinterpretations of classic pieces of theatre. Theatre Critic, Matt Trueman, wrote about this new work in progress in The Guardian. What caught my eye, however, was that their version comes with a twist – it will take place overnight and the audience will be invited, encouraged even, to go to sleep during the performance. You don’t just by a ticket, you buy a bed and meal and there are 3 levels of ‘package‘ available, depending on the amount of comfort you want to enjoy during the ‘show’. The company says of its plans:

It is seems hardly a week goes by now where I don’t read about a piece of immersive theatre playing somewhere in the world, and this week was no exception. The first I’d like to share is news of a UK company, Rift, who are planning to stage a version of Macbeth. The company have a reputation for staging immersive reinterpretations of classic pieces of theatre. Theatre Critic, Matt Trueman, wrote about this new work in progress in The Guardian. What caught my eye, however, was that their version comes with a twist – it will take place overnight and the audience will be invited, encouraged even, to go to sleep during the performance. You don’t just by a ticket, you buy a bed and meal and there are 3 levels of ‘package‘ available, depending on the amount of comfort you want to enjoy during the ‘show’. The company says of its plans:

Face-to-face with witches in an underground car park. Feasting with the Macbeths. Bedding down for the night on the 27th floor as a siege rages around you. Characters sleepwalking through the walls: confiding plots, summoning apparitions and conspiring murder. In the morning waking to find the battle lost or won.

This is William Shakespeare’s Macbeth seen from the inside out. This production like a fever-dream leaves you questioning ideas of space and status; dystopia and utopia; waking and sleeping.

This production scatters the story of Macbeth over one night. From Dusk till Dawn

Felix Mortimer, artistic director of Rift talks in this documentary about how they work – in this case on a production of Kafka’s The Trial.

Meanwhile in Australia, the Perth Festival International Arts Festival is in full swing and immersive is clearly the order of the day with Punchdrunk, Look Left Look Right and Rimini Protokoll are all presenting wildly different immersive work. Punchdrunk’s The House Where Winter Lives is for 3 to 6 year olds, Look Right Look Left are performing a reworking of their city-specific work, You Once Said Yes originally made for Edinburgh and Rimini Protokoll are staging Situation Rooms which requires its audience of 20 to wear headphones and carry iPads.

Australian writer and critic, Jane Howard, wrote about all three shows in her article for the Australia Culture Blog, The Guardian. In it she talks to the creatives behind the pieces.

Perth festival’s immersive theatre: ‘being confused is perfect’

While the headline shows of the Perth festival may be playing to hundreds at a time, in pockets all around the city this week performances are happening on a much smaller scale. These immersive theatre pieces are reliant on the actions of audience members to stage the work: from the solo audience of You Once Said Yes to the tightly choreographed interaction of audience members in Situation Rooms to the rambunctious collaboration of children in The House Where Winter Lives.

Kathryn McGarr, one of the performers with Punchdrunk’s The House Where Winter Lives, tells me that immersive theatre “inspires people a bit more”. And then there’s the practical consideration: even with the best will in the world, faced with a comfy chair in a warm, dark room it’s sometimes hard to stay awake. “People do fall asleep. Whereas there is no way you could fall asleep in a show like this.”

That much is certainly true. The adventure sees Mr and Mrs Winter take the audience of three to six-year-olds on a journey to discover the lost key to the larder. While Punchdrunk have created many immersive works for adults and even older children, this is the first time the company has pitched at such a young age group – and when you see their reactions it’s easy to think that this audience is perhaps the perfect age to be experiencing this work. Entirely without ideas of what “theatre” should be or how you should behave when watching it, they fully invest in the world.

Punchdrunk give the children a high degree of autonomy in their reactions. “We’ve got the script and we’ve got the structure and we’ve got certain things that we can do, and then we know when we can riff a bit and let them fill in the answers,” says performer and co-creator Matthew Blake.

Co-creator and performer Frances Moulds agrees. “There is a journey we need to go on,” she says, “but we can go with whatever they give us … That we’re open is actually a key thing: we’re open to anything they say and we want to hear what they’re saying.”

Allowing for audience response and choice is also central to You Once Said Yes, a show performed on the streets of Northbridge for an audience of one. That person has to be directed to a certain extent, concedes production manager Rosalyn Newbery, but “that has to be done sensitively and without dictating, because their responses and their reactions are very important, and they will change certain things”.

The title, she says, strongly suggests to the audience how to respond. Yet they can still say no, they can take an alternative route from that which is expected of them and the performers and production team must know how to be responsive to that.

James Rowland, one of the performers who travelled with the piece from the UK to join a local cast, says “no one show with one character will ever be the same, just because of the way people talk to them. The number of shows we’ve done is the number of shows there’s been.”

Many immersive theatre pieces rely on these interactions between the audience and performers and the self-direction and personality the audience invests into the work and the world. Rimini Protokoll’s Situation Rooms is the exception to this rule.

The documentary theatre piece invites the audience to step into the shoes of 10 people each as they talk about their relationship with the weapons industry. Following instructions on an iPad mini, with the world on the screen mirroring the environment built by the company, the audience move and silently interact in the exact place of the person whose story they’re hearing.

One of the creators, Helgard Haug, says the precision of the work is integral. “I think everybody understands that it’s perfect if it works, if you’re following it precisely. If you are in a space and you’re sitting at a table and you’re in the story of a person, and in the film you see a door opening and a person entering the space, and if that repeats in the real environment, in the real space where you are that’s the fun of it.”

While they walk through the space Haug wants the audience to question how these people fit into our society and why we each exist in the reality we exist in. After seeing the show, she says “to be confused is very productive. After half an hour leaving this building and being confused is perfect. Being exhausted is perfect. Needing a cup of coffee and a deep breath to then find your own skin again is just a very good thing to do with that content.”

While Situation Rooms aims to highlight the realities of a wider world, You Once Said Yes is about highlighting the realities and personality of the participant. Being involved in the presentation of such immersive work holds “massive privilege” for an actor, says Rowland.

“It’s pretty much the only arena in one-on-one performance where you really get that opportunity [to really meet the audience]: without lights, without a stage, in a situation where you just say, ‘No, go do whatever you want to do. Do your thing within the parameters of the show,’ which is lovely.”

That is one of reasons that people have responded so well to the show, he argues.

“By the end they feel they are, and they have been, valued, and it is about them as much as it is about the stories they’re unwrapping.”

Voices Within

A quick little post from me today. An episode from a BBC World Service programme called The Why Factor.

From sub Saharan Africa to the west coast tribes of Canada to the Mardi Gras of Rio, New Orleans and Venice, masks define realities – of religious belief, of healing power, of theatre and entertainment, of concealment and of memorialisation in death. They have been around as long as humanity and they evoke both fascination and fear. Mike Williams traces the power and culture of masks and asks why we have them and what they mean for us.

From sub Saharan Africa to the west coast tribes of Canada to the Mardi Gras of Rio, New Orleans and Venice, masks define realities – of religious belief, of healing power, of theatre and entertainment, of concealment and of memorialisation in death. They have been around as long as humanity and they evoke both fascination and fear. Mike Williams traces the power and culture of masks and asks why we have them and what they mean for us.

Click the icon below to listen to the podcast. Not entirely related to theatre but fascinating none-the-less.

A Cultural Democracy

For those of you who read Theatre Room regularly you will have noticed my preoccupation of late with the developments, and debate, surrounding live streaming. Now of course this deals with how we consume theatre, not how we make it and this got me thinking about how this technology becomes part of the creative act itself. I know that there have been experiments in the field, and this piece by Jessica Holland, published in The National, an english language newspaper from Abu Dhabi, lays out some of the exciting possibilities:

Internet theatre – immersive, real-time shows with actors from all over the world

The answer is a brand-new art form that is being pioneered by performers in cities such as Tunis, Beirut and Dubai.

“It’s the future,” says the Lebanese writer, actor and director Lucien Bourjeily, who lives and works in Beirut. “At the moment it’s avant-garde, but it will become the norm.”

Last July, Bourjeily collaborated with Elastic Future, an experimental theatre company that started in San Francisco but is now based in London, on a play called Peek A Boo for the London International Festival of Theatre (LIFT). Five actors, playing spies, programmers and online peep-show entertainers, were divided between New York, London and Beirut, improvising dialogue as they interacted via streaming video. Audience members around the world watched in real-time by signing into Google Hangouts or watching the feed on Elastic Future’s web page. They also interacted with characters on Twitter and took part in a post-show Q&A.

“It was a breakthrough,” says Bourjeily of the performance, which followed just a week of online workshops and involved some quick thinking from the actors when there were glitches in the internet connection from New York. “It opened my eyes to so many possibilities for how to create a new type of immersive theatre.”

Erin Gilley, Elastic Future’s artistic director, says she learnt a lot from the experience and is eager to keep stretching the limits of the medium. She’s planning another work for this year’s Lift to be streamed online in July, with actors performing live via webcam from Ghana, Portugal and the United Kingdom.

“Theatre can’t exist without an audience and we’re trying to creatively explore what that means,” says Gilley of the work-in-progress. “The goal is for it to feel like you’re sitting in a theatre with other people, even though watching it will be a private experience.”

Gilley is avoiding screening the feed in an auditorium, in case the process prevents her from “discovering ways to create that feeling online”.

Much like Bourjeily, Gilley is evangelical about the benefits of this new, hybrid art form. For starters, it can bypass censors in countries such as Lebanon, where playwrights are required to submit their work to a bureau for approval. Performing online is cheaper than renting a space and flying in actors and it grants access to audiences from all over the world. It creates novel ways for artists scattered all over the globe to cooperate and to interact with viewers.

It can also turn practical constraints into aesthetic virtues….

As technology develops, the artistic possibilities multiply. “We have new ways of getting emotionally connected to our audience,” is how Bourjeily puts it. “The sky is the limit.”

Lucien Bourjeily is a fascinating man, as his website attests. So much so that Index On Censorship – a global NGO that fights for freedom of expression – has made him one of their four nominees for the Freedom of Expression awards for his play Would It Pass Or Not?, which is about censorship in Lebanon.The play was banned – by the censors, thus forcing them to justify their actions in public.

You can watch Peek-A -Boo here. It makes interesting viewing.

Elastic Future have been commissioned by LIFT to create a piece for this year’s festival, called Longitude, which will be streamed online on 9, 16, and 23 June. Indeed LIFT and it’s artistic director Mark Ball clearly see this kind of work as vital, linking the digital (stage) space with a wider cultural democracy – which is another blog post entirely.

As a post script, one of the other nominees for the Index Freedom Of Expression awards, which are in their 14th year and honour people around the world fighting for free expression, is David Cecil. Cecil is the British theatre producer who was jailed in Uganda for staging a play about homosexuality and whom I wrote about in the posts Stonewalled and A ruling for common sense over a year ago. Appallingly, a month ago the Ugandan parliament passed an anti-homosexuality law which, amongst other things, included punishments of up to life imprisonment. David Cecil is not gay. In fact when he was deported he was forced to leave behind his partner and their two young children. As I write, he has not been allowed to return. The man deserves to be honoured.

Something Else To Stream About

Yesterday morning, at 5.00am, I found myself watching live theatre. It had started at 1.00am and I was just tuning in. It was a live stream of a durational work, 12AM: Awake & Looking Down, by Forced Entertainment. And what a joy it was – my insomniac self isn’t normally this productive. To put it in context,

12am is a physical and visual performance that explores the relation between object and label, image and text…..The piece lasts anywhere between 6 and 11 hours and…..the audience are free to arrive, depart and return at any point.

Although this will be the basis of another post, just for the sake of understanding this one, durational theatre is defined as:

a form through which TIME is manifested in its original (natural) purity and brought to the forefront as pivotal to the experience. The performance is designed so that time, as the primary theme of the piece, physically affects and mentally transforms the performer, the audience, and the space

The particular production lasted 6 hours and although I only watched for just over an hour (the stream to Hong Kong was a little too stuttering to sustain more than that) it was an event that I enjoyed being part of. Both Forced Entertainment and Tim Etchells were live tweeting alongside it, as were people around the globe who were watching too, which added to the experience. It felt very ‘live’, but it was the fact that it was a new ‘experience’, a new type of theatre, that I think I enjoyed it more.

These tweets give you a flavour of ‘how’ people were watching and interacting, and they themselves, for me at least, became part of the narrative as it unfolded.

These tweets give you a flavour of ‘how’ people were watching and interacting, and they themselves, for me at least, became part of the narrative as it unfolded.

Other people, as the tweet above shows, were clearly having the same experience. But it was the one below that really made me sit up and realise what I was actually witnessing.

Other people, as the tweet above shows, were clearly having the same experience. But it was the one below that really made me sit up and realise what I was actually witnessing.

I got more excited by the fact that Tim Etchells, artistic director of Forced Entertainment then tweeted the following in conversation with Matt Trueman, a theatre critic:

It is Etchells’ words about context that really struck home. Having written recently, and at length, in my post Something to Stream About about the emergence of live streaming and broadcasting of theatre, this was adding another layer. The day before I had read a piece, Filmed theatre: a new art form in itself?, by Racheal Castell who is Head of Screenings at Digital Theatre. In it she covers some of the ground I had in my post, but she also observed that

It is Etchells’ words about context that really struck home. Having written recently, and at length, in my post Something to Stream About about the emergence of live streaming and broadcasting of theatre, this was adding another layer. The day before I had read a piece, Filmed theatre: a new art form in itself?, by Racheal Castell who is Head of Screenings at Digital Theatre. In it she covers some of the ground I had in my post, but she also observed that

The stage is indeed a precious space, and what happens between actor and audience member therein is both magic and real. But we mustn’t forget that plays are both ephemeral and eternal. A play is written to be performed, but performed again and again on new sets by different actors in reimagined contexts. The tension between the live and the repeated is inherent to most theatre.

Although the point isn’t entirely relevant to this post, the last sentence does connect. However, this second point by Castell is very relevant:

It was more gratifying to witness the responses to our watch-alongs, where people around the globe tune in and press play on a production at the same time and are suddenly able to visit the West End, albeit virtually. It’s as though the breath formed to articulate a Shakespearean monologue, the energy emitted between an ensemble, the tear that falls from a performer’s eye, is the butterfly’s wing and we – with all our technology, our media, our distance, our global experience – are the hurricane.

She is referring to an experience, not unlike watching 12am for me. Digital Theatre’s watch-alongs are dependent on social media, both to generate an audience all watching remotely at the same time as well allowing for a communal commentary along the way. Twitter replaces the real life audience, so rather than turning to your fellow theatre-goer for affirmation of a shared experience, you tweet it instead.

It’s also just struck me – a little off the point – that watching theatre in this way gets rid of the errant rings and glaring screens of mobile devices, hacking coughs, sweet wrappers being opened and latecomers that pervade the ‘live’ experience.

Castell (and many others I have read recently) are struggling to define this new live theatre experience, let alone give it a name. Whatever we eventually end up labelling this vanguard movement, I know I will be in the front row.

I want finish this post with another comment about 12AM, this time from Instagram. It says it all:

A Fine Line?

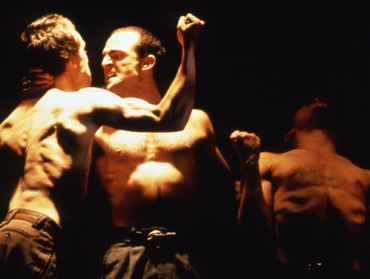

So is it theatre or dance?

This is a question I often find myself answering. Actually, to be precise, is a question I encourage my students to find an answer to for themselves. DV8, Tanztheater Wuppertal, SITI and ZenZenZo are amongst the companies around the world that fall into neither one camp or another. In the West this issue with classification is perhaps more significant than here in the East where ancient theatre traditions tend to be dance based. Even more contemporary theatre movements in Asia have a more dance related aesthetic, butoh being a perfect example.

DV8 says of itself that their ‘work is about taking risks, aesthetically and physically, about breaking down the barriers between dance and theatre’. In its philosophy, SITI says that ‘The theater is a gymnasium for the soul’ and of course Butoh is also called the Dance of Darkness’.

So what do we do when a form defies classification? Well, we call it physical theatre of course, the broadest of all definitions that is so over-used it is almost meaningless. It was therefore with great interest that I read a piece written by Katie Colombus, for The Stage entitled Let’s get physical with dance.

In it, Colombus explores her own assumptions about where the line is drawn -‘I generally belong to the art is life, movement is dance school of thought – if it’s physical then it’s dance, and theatre for the most part is always physical (unless we’re talking floating Beckett heads but this is rare in the extreme)’. She had been to see a piece by LA based company, Wilderness, called The Day Shall Declare It.

Let’s get physical with dance

I often have to answer the question “but why did they train in dance to do that? That wasn’t exactly dancing, was it?” when seeing contemporary work.

This week the roles were switched around when I went to see The Day Shall Declare It, a physical theatre piece by LA company Wilderness, choreographed by Sophie Bortolussi. I was interested to see how non-dancers would cope with choreographed movement, and how theatre with elements of movement is different from physical theatre, is different from dance.

I generally belong to the art is life, movement is dance school of thought – if it’s physical then it’s dance, and theatre for the most part is always physical (unless we’re talking floating Beckett heads but this is rare in the extreme).

The Day Shall Declare It is made up of Tennessee William scripts interspersed with choreographic interludes. The performers are not dancers, they are actors, and although some scenes look like dance phrases, there is a distinctly physical tone to the experience that is really very different from the dance work I’m used to:

More raw, less polished, not perfectly hitting steps or sequences, but committing to the physicality nonetheless.

It adds to the play an extra dimension of communication that really brings home certain points – the seductive tango of when a couple first meets in a post-depression dance hall; lifting and moving around each other in close quarters adding to the claustrophobia of their narrative, reaching upwards and outwards of their small-town banal existence; slamming against window boxes and flinging/falling face first over leather rocking chairs while quaffing bourbon in a squiffy homo-erotic party scene.

Artistic director Annie Saunders is articulate in her reasons for using physical theatre to make a point:

When the recession hit, the personal, private question of the meaning of working – “what do I want to do?” versus “what will I live on?” – seemed to become immediately, drastically public. I wanted to make a piece that explored this and looked to a similar historical moment, the Great Depression, and the extensive canon of American labour plays.

This piece is an effort to creatively conflate these period texts with a free-form theatrical model and contemporary movement score, echoing the responses of the current moment, such as Occupy Wall Street, which for me took on a powerful and spontaneous choreography of its own.

Theatre expressed through movement is rather more sophisticated than merely being mime (thank you, Barrault). Part of it is the focus on the body, the unctuous flow between narrative, physicality, storytelling and expression from actor to actor and to the audience. The best thing about it is the fact it isn’t a slave to music or time signatures or phrases, it can flow purely from the momentum of the moment.

As far back as Artaud, theatre practitioners were encouraged to have a closer experience with the actors – scripts and spoken word alone being a metaphorical barrier to the audience. Since then physical theatre has thrived under DV8, Matthew Bourne’s Play Without Words, Motionhouse, Clod Ensemble and Theatre De Complicite, to name but a few, all companies fluent in both verbal and physical dexterity. Here the actors certainly have a more direct relationship with the audience, we are spoken to, moved around the space, sat by.

Part of it is how the piece has been created – often through group improvisation rather than simply reading parts. It’s an experience that brings you closer to your castmates in terms of proximity, intensity and impact. There is an excitement and chemistry that is palpable, particularly when in closer quarters to the cast (as is the case with Wilderness) – their collective energy and connection.

In essence the performance is more conceptual than a straightforward play, but it’s performed in a way that is intriguing and alluring. The integration of disciplines allows for further development of words, bodies and acting techniques. Expression and gesture can grow and when repeated the experience becomes more ritualistic, there are more layers to peel back.

The Day Shall Declare It hints at stories and alludes to events in distinct sections that don’t need to be understood in the way as linear narrative. It is more than enough to experience than to understand, as their reviews prove. Movement and speech are ultimately two instruments used for the same purpose – communication to an audience. Together, they are a powerful tool.

Something to Stream About

Over the course of the last few months I have been carefully watching the growing debate surrounding the showing of live broadcasts or recordings of theatre in cinemas and live streaming to anywhere you want to watch.

Theatre has generally resisted these modes of reaching a wider audience, although opera, particularly the Metropolitan Opera in New York and the Royal Opera House in the UK have been pioneering it for a number of years. It comes as no real surprise that live streaming has started to take hold and is expanding rapidly. Cinema-based and arts venue showings are on the increase as well as specific services, like Digital Theatre which allow for anytime, anywhere access to a growing range of live filmed, but post-produced, edited performances.

It would appear that the UK is leading the charge, followed closely by certain North American companies. National Theatre Live started the ball rolling in the UK in 2009 showing live performances in cinema’s across the country:

National Theatre Live is the National Theatre’s groundbreaking project to broadcast the best of British theatre live from the London stage to cinemas across the UK and around the world.

Though each live broadcast is filmed in front of a live audience in the theatre, cameras are carefully positioned throughout the auditorium to ensure that cinema audiences get the ‘best seat in the house’ view of each production. Where these cameras are placed is different for each broadcast, to make sure that cinema audiences enjoy the best possible experience every time.

Satellites allow the productions to be broadcast live, without delay, to cinemas throughout the UK as well as many European venues. Other venues view the broadcasts ‘as live’ according to their time zone, or at a later date.

They have rapidly expanded the programme and now broadcast co-productions, as well as their own work, from across London. The statistics are impressive – seen by 1.5 million people in 500 venues around the world, half of which are outside the UK.

.

The article that really got me thinking about the implications of it all, from early 2013, was written for Exeunt by A.E Dobson, Live to Your Local Cinema – Michael Barker. In it, Dobson notes that this nascent form

……has attracted little critical or academic interest despite its profile. Whilst the current paucity of literature can be attributed to sheer novelty, its cause is certainly hindered by its lack of a name. Those working within the film industry have found it useful to use the term “alternative content”; those without hanker after a moniker more focussed on what the format does rather than what it doesn’t.

He goes on to say, and this is probably at the core of any subsequent debate and discussion, that

While some aspects of Livecasting may allow a greater number to claim ownership of the ritual, film is at the same time a fundamentally distancing medium; it positions the cinemagoers – structurally – as outsiders, a problem that the architects of the experience spend a good deal of time repressing.

The debate in the UK was really ignited by the decision of the Royal Shakespeare Company to start broadcasting to cinemas too, alongside the National Theatre broadcasting it’s anniversary performances on BBC Television. First to write about this was Dominic Cavendish in The Telegraph with a piece simply entitled, Should live theatre be shown in cinemas?

At around the same time Pilot Theatre live-streamed, for free, its production of Blood and Chocolate, an immersive, promenade piece which is still available to watch on Youtube. It is here that differences start to occur. The National Theatre and The RSC are only making their broadcasts available at a specific time, in a specific venue while Pilot are making theirs available at anytime as long as you have access to a computer. More about Pilot later.

Almost simultaneously came the news in an article in the Canadian Globe and Mail, entitled Stratford Festival to film productions for worldwide theatre distribution, that the Southern Ontario Festival was planning to do something similar with a view to international viewing.

At this point the debate got interesting. The Guardian in the UK, in its editorial pages, wrote that:

In praise of … streaming live theatre

Nothing beats being there, as any sports fan knows, but there are consolations when barriers to theatre access are removedOn Wednesday night the Royal Shakespeare Company joined the growing band of arts organisations that are breaking down the biggest single barrier to access – the need to be there – by transmitting live their top-rated Richard II to cinemas around the UK. Audiences from Aberdeen to Ambleside, Taunton, Tamworth and Thurso – and many more in Ireland, Sweden, Canada and Malta – were simultaneously connected to Stratford for a three-hour rollercoaster ride through medieval England. Thousands of enthusiasts who could never otherwise have got a ticket were able to see the first of director Gregory Doran’s new cycle of Shakespeare’s history plays. Nothing quite beats being there, as any sports fan knows. Yet sometimes it felt almost better: the camera could close in on Richard’s ravaged face, and it could reveal the austere splendour of the gothic set: a seat in the gods and the front row. Being there can’t do that.

This perspective really struck a chord with me. I’ve been to see too many plays where I know I missed the subtleties of the performance because I simply been too far away from the stage – particularly a problem in more modern, larger venues. However, and not surprisingly, there have been those people who simply can’t see the value of live-streaming, even fearing that it will reduce theatre-going audiences rather than increase them. In The Stage last week (the newspaper for theatre professionals in the UK), an executive from a regional theatre labelled the NT Live screenings as ‘Weird’

Stephen Wood ……. warned that the National Theatre’s NT Live initiative must never become a “substitute” for actual theatregoing.

Wood, who worked as head of press at the National in the 80s, has labelled the screenings “weird”, adding: “They are neither theatre nor film, but something in between. That’s not to say they are not valid, it’s just that they are a very odd thing.”

The article, NT Live must not become a “substitute” for theatregoing, goes on in the same vein. However, the accompanying survey and comments would seem to disagree with Wood. Not surprisingly his comments garnered some criticism. My favourite is from the ever pragmatic Lyn Gardner in her Guardian Theatre Blog. This was written only a few days after Wood’s comments, and another live streaming event by an independent theatre, this time of Howard Brenton’s latest play, Drawing The Line, which explores the moment when the line between India and Pakistan was made and British rule in India ended.

Why digital theatre poses no threat to live performance

The early 20th-century conductor Sir Thomas Beecham was not a big fan of the radio. He thought that if people could listen to concerts relayed in their own home, they would be reluctant to visit concert halls. He chided the “wireless authorities” for doing “devilish work”.

I thought about Sir Thomas – who no doubt would be delighted to learn that the devilish Radio 3 hasn’t killed off the live concert – last week when Stephen Wood, executive director of the Stephen Joseph theatre in Scarborough, was reported in the Stage as taking issue with NT Live, which screens productions live to venues across the country and the world.

Upcoming productions include the Donmar’s sellout Coriolanus with Tom Hiddleston. In a single evening, Coriolanus could stream to more people than it will play during its entire run in the 250-seater venue. Wood is concerned that these kind of broadcasts will become a substitute for actual theatregoing, saying: “We must be careful that we don’t arrive at a situation where this type of thing is what people’s only experience of live theatre really is.”

Wood’s comments echo those of Michael Kaiser of the Kennedy Centre in Washington, who in a blog last year raised the spectre that digital downloads and screenings are threatening American regional theatre. He asked whether the baby-boom generation could be “the last to routinely attend live, fully professional performances” and suggested that the allure of being able to broadcast to huge numbers could make organisations who are using digital technology risk-adverse and lead to the collapse of regional theatre. Why will people go out to the theatre, particularly at a time of rising costs, he asks, when they can stay home and download or go to a local cinema? Probably for exactly the same reasons why live gigs are flourishing. Downloading your favourite band’s tracks is not the same as seeing them live.

In both cases, Wood and Kaiser appear a little like King Canutes trying to fruitlessly hold back the waves. In both cases they appear to see digital as a threat to live theatregoing. Perhaps assuming that the 60,000 people who attended live screenings of David Tennant’s Richard II in cinemas are incapable of understanding that it’s not the same as actually seeing a live performance at the RST or the Barbican. I know perfectly well that fresh salmon and smoked salmon don’t taste the same but that doesn’t stop me from wanting to sample both.

Not everyone has a theatre on their doorstep or indeed access to it. Many of the thousands of British schoolchildren who last November enjoyed a classroom streaming of Richard II and a live discussion with Tennant and Greg Doran would not otherwise have had the opportunity to see the show at all.

But that doesn’t mean that their appetite won’t be whetted to go to their local theatre and see a different show as a result. Early research about NT Live found that it was more likely, not less likely to make people go to the theatre, and people who go to the theatre are more likely to go and see more theatre.

More forward-thinking theatres understand this. They are not in competition with each other for audiences, and anything we can do to encourage theatregoing and make it a habit can only be good in what ever form it is distributed. Surely we should be celebrating the fact that the NT reached two million more people through screenings, not getting anxious about it? If anything it should be a spur to make theatres and companies all over the country wonder how might they might use of digital in interesting ways. Many already are. Some are looking at different ways of storytelling in projects such as Unlimited’s new initiative, Uneditions. I don’t think this is an issue that necessarily pits big against small, or London against the regions. It is more about open-mindedness and a willingness to be bold.

It’s certainly not about ditching the way that theatre has been toured and delivered over hundreds of years, but rather about seeing the artistic possibilities of digital platforms and extending reach, capacity and audiences. There are plenty, from Pilot to National Theatre Wales and Hampstead, who are already doing just that. If they can do it then so can the Stephen Joseph, and others too.

Michael Kaiser’s blog for The Huffington Post, that Gardner references, makes interesting reading, but is very doom laden. He suggests that the broadcasting by national companies will inevitably bring about the demise of smaller regional companies. However, he makes assumptions and asks questions with very little insight of the UK experience where it is regional and smaller companies who are embracing live-streaming to widen their audience base and bring in more people to their building-based work. I agree with the veritable Lyn Gardner completely. The mother of a friend of mine who is a regular theatre-goer, but doesn’t live in London, now watches the NT Live productions at her local cinema, but still goes to London to watch other productions, by other companies.

I’m not going reiterate all the positive and supportive arguments made here in the articles and links, but to be able to increase the reach of a piece of work, both nationally and internationally, can only be a good thing. For example, the global live streaming of another of Howard Brenton’s plays last year, The Arrest of Ai Weiwei, has value beyond that of being an artistic and creative sharing. In the UK it means that people living outside London have access to some of the best theatre in the world and those regional companies with smaller budgets, doing exciting things, can have a reach way beyond their original remit, community and intent. The same will be reflected in any country where national theatrical institutions are based in a capital city, but are geographically and/or financially out of the reach of most of its citizens.

With that in mind, Marus Romer, artistic director of Pilot Theatre, announced the launch of a new a project, via his blog, that aims to create a country-wide live streaming service, LiveTheatreStream.TV. Pilot have been pioneering live-streaming of their work and creative conferences for a while now and have a dedicated digital production team. I have posted this before, but here again is their live stream of Blood and Chocolate.

.

Clearly, having said all of this, what we see now is a variety of broadcasting/streaming options emerging:

- Some are streamed live, are free and can be watched again later via a hosting site/computer

- Some are streamed live, are free and can be watched for a limited time only, again via computer.

- Some are recorded, then edited and then made available for streaming, but at a charge via a subscription service

- Some are broadcast live (via satellite) to specific venues, mostly cinemas, and are charged for but are not accessible in any other form

- Some are recorded live, then broadcast later to specific venues, mostly cinemas, and are charged for but are not accessible in any other form.

I find it all fantastic and exciting for so many reasons. As a theatre teacher, for so long I have had to make do with filmed versions of plays or one camera set-up recordings of live productions – neither of which are anywhere near satisfactory. As an English speaking theatre practitioner and theatre-goer living internationally, I am, of course, delighted by these developments. Having said that I am, so far, always disappointed when I go to the NT Live website and it tells me that I am 7,500km from my nearest cinema – the distance between Hong Kong and Melbourne, Australia. Mind you, this morning as I was writing, I have been back to the site and it is telling me that the broadcast venues are getting closer – I can apparently now watch Frankenstein and Coriolanus in Japan, the Philippines and South Korea – so now only 1,100km away. One can but hope.

My original intent was to finish the post at this point, but as I said at the beginning and have hopefully alluded to throughout, the whole ‘genre’ is continually evolving, as are the discussions around it. However, a Tweet from yesterday led to another avenue of discussion, which very meaningfully adds to the debate about how we adapt the cultural landscape to take advantage of and make the most of live streaming. Elizabeth Freestone, artistic director of a well regarded small scale British touring company, Pentabus, wrote a blog yesterday, What live theatre screenings mean for small companies which, while supportive of what is happening, raises some very relevant, pertinent questions about the future. Whilst Freestone’s comments are about the UK, they could easily have a relevancy elsewhere as things develop.

I run Pentabus, a small-scale touring company. We tour rural area – village halls, fields, colleges and pubs – taking our work into the heart of a community. We do this because people living in geographically isolated places struggle to have the same access to live arts their urban counterparts enjoy. Transport, pricing, time – all conspire to deny opportunity. So I’m thrilled live screenings give our audiences more opportunities to experience theatre near them. And I’m delighted the income venues get from live screenings (including bar sales) helps them afford to programme more live theatre in turn. But some of the infrastructure surrounding screenings can’t help but pitch one against the other. And if put into competition with each other, venues will always choose live screenings because they are much cheaper to buy than live theatre. The good news is, the problems are solvable.

No doubt the debate will continue. Your thoughts?

East meets East

A quick post to share an item from the BBC Hindi service, about the growing experimentation with physical theatre in India. The report is from the The Bharat Rang Mahotsav International Theatre Festival of India which is in its 16th year and features a Butoh inspired piece, Maya II.

Physical theatre draws attention of theatre-lovers in India

Theatre in India has often been deeply traditional, using storylines, dialogue and song to reflect issues in society.

But over the last few years at the annual theatre festival held in Delhi, a different type of production has been gaining popularity.

Inspired by their international counterparts, Indian directors are experimenting with forms of physical theatre which use light, sound and body movements to tell the story.

Click the image below to see the report by Divya Arya

No Longer A Refugee

The article I want to share in today’s post really touched a nerve when I read it last week. It was published in the Financial Times, written by Charlotte Eagar, and is about her project to stage the antiwar Greek tragedy, The Trojan Women with a cast of Syrian women who have fled their homeland’s vicious civil war for neighbouring Jordan.

If you don’t know the play, The Trojan Women is about refugees, set at the fall of Troy. All the men are dead and the former Queen Hecuba of Troy, her daughter Cassandra and the rest of the women are waiting in a refugee camp to hear their fate. Euripides wrote the play in 415BC as an anti-war protest against the Athenians’ brutal capture of the neutral island of Melos; they slaughtered all the men and sold the women and children into slavery. You can download the text of the play as an e-book here, or read it online here.

Eagar’s piece is definitely worth reading. It charts the whole project from beginning to end. It is both immensely inspirational and gut-wrechingly sad. Click the link below for the full article.

Syrian refugees stage Euripides’ ‘The Trojan Women’

You get a real sense of the power of the performance in the interview, below, with one of the actor refugees, known simply as Fatima.

.