Today I am sharing a really interesting article by Simon Callow entitled Stanislavski was racked by self-doubt. It was published this week in The Guardian and I reproduce it here in full.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of the Russian actor, director and theorist, Konstantin Stanislavski. If the anniversary is remembered at all, it will be with quiet respect. There was a time – not a time out of memory, though it seems distant now – when furious battles were waged in the theatre about acting: what it was and what it should be. In green rooms, in drama schools, and in the fiercely polemical pages of the theatre magazine Encore, the debate raged. It started around the time of the foundation of English Stage Company at the Royal Court theatre in the mid 1950s and continued until some point in the late 1970s, when all ideological and aesthetic discussions were abandoned in the face of economic trauma. The principal figures around whom the antagonists grouped were Stanislavski and the playwright and director Bertolt Brecht who, in the 1920s and 30s, articulated a theory of acting to rival, and indeed to oppose, the Russian’s. Broadly speaking, Brecht’s approach was political, Stanislavski’s psychological; Brecht’s epic, Stanislavski’s personal; Brecht’s narrative, Stanislavski’s discursive. Brecht’s actors demonstrated their characters, Stanislavski’s became them; Brecht’s audiences viewed the actions of the play critically, assessing the characters, Stanislavski’s audiences were moved by the characters, identifying with them; Brecht’s productions were informed by selective realism, Stanislavski’s aspired to poetic naturalism.

As Stanislavski had done with his Moscow Art theatre, Brecht created an acting group, the Berliner Ensemble, whose practice embodied and demonstrated his theories; the Ensemble’s visit to London in 1956, the year of Brecht’s death, had a seismic effect on British theatre, an effect that only started to fade in the last years of the 20th century. The Moscow Art theatre, meanwhile, had started to calcify; when Stanislavski’s original productions, still in the repertory, came to London they seemed preserved in aspic. Brecht and his theories made all the running, both aesthetically and politically, chiming with the British leftwing puritan tradition, resulting in productions that were bare, cool, politically explicit. The German’s influence, first felt in Joan Littlewood’s productions, was a formative factor in the unique populist style she forged for her Theatre Workshop; it informed a great deal of the Royal Court’s house style, in physical productions, in new plays, and in acting. It was also at the root of Peter Hall’s new Royal Shakespeare Company, and – sometimes a little incongruously – became part of the many-hued fabric of Laurence Olivier’s National Theatre Company, which produced a number of Brecht’s plays, performed new plays (by John Arden and Peter Shaffer, for example) heavily influenced by him, and applied his lessons to classics such as Farquhar’s The Recruiting Officer, starring Maggie Smith, who proved to be a brilliant, if somewhat unexpected, Brechtian.

But Stanislavski had been a force in the British theatre long before Brecht. His system had been taught in drama schools from the 1920s, and, slowly at first, but increasingly, leading British actors embraced his quest for psychological truthfulness over mere theatrical effectiveness. John Gielgud, Peggy Ashcroft, Michael Redgrave – but not, significantly, Olivier – endorsed his work; after the war Paul Scofield did the same. The huge popularity of 1950s film stars such as Montgomery Clift, Marlon Brando and John Garfield gave currency to the extremely limited version of Stanislavski’s system created by their teacher, Lee Strasberg, who coined the phrase The Method for his Stanislavski-lite version of it. Essentially, Strasberg elevated one aspect of Stanislavski’s work – emotional truthfulness – into the whole theory. Not only was this a crude reduction, it ignored the constant development and refinement of the theory, which preoccupied the Russian until the day he died, weighted down with international honours, in Moscow, in 1938. But by then the Soviet cultural nomenklatura had started the process of ossification that led to the lifeless productions London saw in the 1960s, a bitter paradox for a man whose entire life in art had been an unceasing quest for renewal, an unending struggle against the formulaic, the conventional, the self-referential.

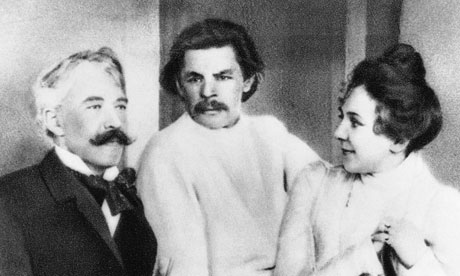

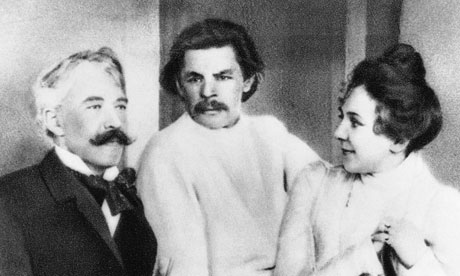

In fact, Stanislavski’s life had been a series of paradoxes. Born Konstantin Sergeievich Alexeyev, the scion of a wealthy merchant family with interests in fabric, Stanislavski (he changed his name to avoid the obloquy that a career in the theatre might have brought on his family) was fascinated by acting from his earliest days, though he was always troubled by a certain self-consciousness, except, he noted, when imitating other actors, and then, he said, he was just plain bad. He acted enthusiastically with his fellow amateurs in the group known as the Alexeyev Circle, which he had founded when he was 14; he directed the plays and invariably took the leading role. Thanks to his insistence on the highest levels of presentation (bankrolled by his family), the group was a great success, and Alexeyev, as he still was, was prevailed on to become the head of one of the imperial dramatic schools. While there, he met Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, who was running a school himself. The meeting at which they discussed the possibility of founding a theatre company lasted 18 hours, ending at Stanislavski’s house just outside Moscow the next day. Nemirovich-Danchenko, a highly cultured man, sophisticated and worldly wise, had written several successful plays; Stanislavski was something of a naif, with poor literary judgment and little social ease. Despite differences in background and temperament, they found themselves in such intense accord on every topic concerning the faults of the Russian theatre and the remedies for them, that the theatre they had convened was born there and then. The question of division of labour within what they decided to call the Moscow Art theatre was answered by the formula suggested by Stanislavski and was, subsequently, troublesome: he was to have responsibility for form, Nemirovich-Danchenko, content.

Their first production, a historical epic by Alexei Tolstoy, was a success, largely due to the painstaking research undertaken for the costumes and set. Subsequent productions were less successful, including a Julius Caesar with Roman costumes and settings of impeccable archaeological credentials but that never came to terms with the play. Several productions were cancelled because of problems with the censor. The men quickly came to the point where they had to either have a huge success or sink forever: Nemirovich-Danchenko proposed that they perform a play that had flopped at its premiere, The Seagull, by short-story writer Anton Chekhov. Somewhat against his will – he neither liked nor understood the play – Stanislavski agreed. When the time came to stage it, he withdrew to his dacha, sending his elaborate mis-en-scene back to Moscow page by page, while Nemirovich-Danchenko rehearsed the actors – minus Stanislavski, who was playing the crucial part of the writer, Boris Trigorin.

Their first production, a historical epic by Alexei Tolstoy, was a success, largely due to the painstaking research undertaken for the costumes and set. Subsequent productions were less successful, including a Julius Caesar with Roman costumes and settings of impeccable archaeological credentials but that never came to terms with the play. Several productions were cancelled because of problems with the censor. The men quickly came to the point where they had to either have a huge success or sink forever: Nemirovich-Danchenko proposed that they perform a play that had flopped at its premiere, The Seagull, by short-story writer Anton Chekhov. Somewhat against his will – he neither liked nor understood the play – Stanislavski agreed. When the time came to stage it, he withdrew to his dacha, sending his elaborate mis-en-scene back to Moscow page by page, while Nemirovich-Danchenko rehearsed the actors – minus Stanislavski, who was playing the crucial part of the writer, Boris Trigorin.

Eventually he returned, the play opened and was a huge success. Stanislavski’s flair for creating atmosphere had resulted in an entirely new theatrical experience, in which the voices and characters were elements in an embroidery of sounds of nature and daily life, while the action was broken up to create the maximum poetic effect from the pauses and disjunctions of household routine; great ingenuity was exercised in filling these pauses with physical actions that would justify them. A hypnotic effect, a mirage of real life, was created: not strictly naturalism, but a poetry of the everyday.

The production’s success saved the theatre, which thereafter adopted the symbol of a seagull as its mascot. The author, however, though pleased his play had been liked (especially in comparison to its disastrous first production in St Petersburg) was far from happy with the staging, later ribbing Stanislavski by saying in his earshot that his next play would be set in a country where there were no crickets or mosquitoes to interrupt people trying to make conversation. Chekhov felt, too, that Stanislavski had misconceived the character of Trigorin. This was a recurring theme in Stanislavski’s career, both as director and actor: he had a habit of mentally substituting another play and another character, drawn from his own imagination, for the play and the character the writer had actually written. His literary sense was always poor; he was not an avid reader. Indeed, according to Nemirovich-Danchenko, he was technically dyslexic. He had great difficulty with words (learning them, even speaking them); off stage, too, he was famous for using the wrong word or for not being able to remember the one he needed. To what extent this influenced the development of his system, which often seems suspicious of language, is an interesting question.

Stanislavski was impelled to develop his system because of his dissatisfaction with the work he and his fellow actors were doing in the repertory that succeeded The Seagull: the three remaining plays of the Chekhov canon, Uncle Vanya, Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard, and the first plays Maxim Gorky wrote for them. Stanislavski felt the company’s acting – his own as much that of his fellow players – remained painfully self-conscious and imitative; it lacked the pure “truth” he conceived of as the prime object of the actor’s art. From his earliest years, he had been plagued by the sense of self-consciousness: tall, handsome, graceful, intelligent, he was everything but spontaneous. Nemirovich-Danchenko describes what a favourable impression Stanislavski made on him at their first meeting: how serious, how thoughtful, how unlike an actor he seemed, neither loud nor vulgar nor self-promoting. The impression above all was of naturalness; the result, Nemirovich-Danchenko observes, of many hours practising in front of the mirror. By all accounts Stanislavski was richly endowed by nature to act. Throughout his autobiography, My Life in Art, however, he frets about not having been a great actor. It’s clear that if he had stopped thinking about it for a moment, he would have been. He saw this in himself, and attributed it to his fellow actors. The harder they worked, the worse they seemed to get. Exhausted – he had played the leading part in most of the productions, as well as devising the mis-en-scene for many and directing others – in 1910 he took a sabbatical year to try to solve the riddle.

He spent much of that time in Italy, closely observing great actors such as Tommaso Salvini and Eleanora Duse and trying to fathom what appeared to be their effortless inspiration. He came to the conclusion that they believed in what they were doing, and this belief gave them the capacity to be true to their inner emotion, despite the public nature of the stage; it created great relaxation, too: they seemed not to suffer from tension. At this point, Stanislavski turned his eyes on himself. Was he relaxed? Hardly ever. Did he believe in what he was doing? Almost never. But when had he been relaxed? When had he believed in what he was doing? When had he been good? He remembered certain passages of certain performances he had given. Why had they been remarkable? Generally, he discovered, because they were specific, rooted in either personal experience or memories of behaviour that had impressed him. This seemed to be the key. What if an entire role were to be constructed in this way? One would believe in every minute, and then relaxation would naturally follow: not an externally achieved relaxation, which he knew from trying made little or no difference to the performance, but a genuine, spontaneous freedom.

Something else that differentiated these great actors from – well, from him, for example – was that they knew why they did what they did. Their characters seemed to do everything for a reason: they always seemed to want something, and every action was for the achievement of this want. So there was another principle. Armed with his discoveries – the principles of belief based on the use of personal memories, relaxation and action – he triumphantly announced them to the convened actors of the Moscow Art theatre group. “I have discovered the principles of Art!” he cried. “Oh no, you haven’t,” they replied. “Acting’s not like that at all.”

From that point on, Stanislavski was something of a stranger in his own house. His relationship with Nemirovich-Danchenko, always fraught, became openly hostile, especially after the latter (by now a Communist Party member and head of all of Moscow’s dramatic theatres) publicly humiliated him by taking the leading part in The Village of Stepanchikovo away from him at the dress rehearsal, telling him he had failed to bring it to life. The company itself, during the turbulent years of the post-revolutionary period and the civil war, spent a great deal of time touring Europe and America. Abroad, the Moscow Art theatre was synonymous with Stanislavski, and his work (both as director and as actor) was universally acclaimed; his books, often clumsily translated and eccentrically published, became highly influential. Back in Moscow, he was increasingly marginalised. He eventually created the Studio theatre in which to test and establish his ideas, and then a Second Studio and finally a Third. Over the remaining 25 years of his life he taught more and more, modifying, adapting his principles, but never doubting the truth of those first discoveries. The founder members of the company never quite came round to them, and when they worked with him, he had to bargain with them, offering them large parts in his productions if they would agree to think in terms of the beats, actions, activities and affective memories. The younger actors embraced his ideas enthusiastically, but they then outstripped him in boldness and experiment; again he felt isolated within his own company, although, as he had always done in the past, he came to acknowledge their vitality and renewed himself by advancing into their territory with a radical and controversial production of The Government Inspector.

Meanwhile, he pushed his work further and further away from a simple-minded insistence on the primacy of emotion and psychology, exploring physical action and the crucial importance of rhythm in acting. These later developments have scarcely penetrated into western drama training, though they continue to be used and explored in the former eastern bloc, as has the work of Stanislavski’s pupils, and the results can be seen in the astonishing drama produced in that region, by theatres such as the Rustaveli theatre of Georgia, the Vilnius State Youth theatre, the Maly theatre in St Petersburg. It can also be seen in the impulse towards so-called physical theatre so typical of British theatre in the last couple of decades. In the west, Stanislavski’s work in its earlier phases is mostly deployed in drama schools. And it is here that it has been deeply influential. Because the majority of actors in the mainstream work within the bounds of psychological realism, particularly in TV and on film, Stanislavski’s formulation of the principles of acting is the foundation of most actors’ approach: connecting the emotional life of the character with one’s own; identifying their wants and actions; seeing how they fit into the play or script. Stanislavski was the first to identify these things, and to formulate a way in which actors could work on them, beyond imitation or intuition.

Brecht’s notions that acting is the servant of the story and that the audience needs to know no more of the character than is necessary for the comprehension of the narrative; that gesture is the actor’s key tool, and that the quest for the crystallising gesture is his or her main task; and that making the audience aware of the contradictions of the situation being represented is the purpose of the theatrical event seem not to have endured.

Stanislavski’s fascination with human character, its diversity and complexity, has endured, though there remains, embedded in his system, a deep suspicion of actors and their ingrained proclivity for self-consciousness, for superficiality, for the conventional and imitative – the things of which he so profoundly suspected himself. His star pupil, Michael Chekhov, though he subscribed to Stanislavski’s analysis of acting, had a different view of actors. He believed actors should preserve in themselves their first joyous impulses towards acting – at school, at home, in the street – their natural ease of assumption of character, their fantasy, their ready connection to their imaginations, and that out of that would come the sense of natural freedom that Stanislavski found so elusive. Playful Stanislavskian acting, fantastical Stanislavskian acting – now that’s something to consider. The part of him that knew spontaneity was at the heart of acting would surely have warmed to that.