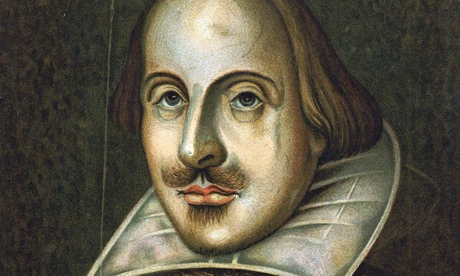

As much of the world begins a new academic year, so does Theatre Room. I am going to pick up where I left off in August with a further two articles that were published as a result of comments made by Ira Glass about Shakespeare and his relevance to a contemporary audience.

As much of the world begins a new academic year, so does Theatre Room. I am going to pick up where I left off in August with a further two articles that were published as a result of comments made by Ira Glass about Shakespeare and his relevance to a contemporary audience.

The first one that particularly caught my attention was written by Noah Berlatsky for The Atlantic. In it, Berlatsky talks about Shakespeare’s political conservatism and how this shaped his writing.

Ira Glass recently admitted that he is not all that into Shakespeare, explaining that Shakespeare’s plays are “not relatable [and are] unemotional.” This caused a certain amount of incredulity and horror—but The Washington Post’s Alyssa Rosenberg took the opportunity to point out that Shakespeare reverence can be deadening. “It does greater honor to Shakespeare to recognize that he was a man rather than a god. We keep him [Shakespeare] alive best by debating his work and the work that others do with it rather than by locking him away to dusty, honored and ultimately doomed posterity,” she argued.

Rosenberg has a point. A Shakespeare who is never questioned is a Shakespeare who’s irrelevant. And there are a lot of things to question in Shakespeare for a modern audience. One of those things, often overlooked in popular discussions of his work, is his politics.

Shakespeare was a conservative, in the sense that he supported early modern England’s status quo and established hierarchy, which meant defending the Crown’s view of divine monarchical right and opposing the radicals, often Puritan, who questioned it.

For all the complexity and nuance of Shakespeare’s plays, his political allegiances were clear. James I was his patron, and Macbeth in particular is thought to be a tribute to the King. It even includes a reference to the Gunpowder Plot assassination attempt at James. That reference is made by Lady Macbeth as part of her effort to convince her husband to murder Duncan. The villainous traitors in the play are thus directly linked to traitors against James.

Macbeth isn’t a one-off to flatter the King, either: Rebels and usurpers in Shakespeare’s plays are always the bad guys. When Hamlet spits out the lines:

Oh fie, fie, ’tis an unweeded Garden

That grows to Seed: Things rank, and gross in Nature

Possess it merely.The vision of sickening wrongness there is in part repulsion at his mother marrying his uncle, but it’s also a political disgust at the fact that the rightful ruler is gone, replaced by a usurpur. What’s “rank and gross” is not just sexual impropriety, but perversion of divine order. The Tempest is about restoring the rightful Duke to his place in spite of his usurping brother, while Othello shows that Shakespeare’s sympathies are not just with kings, but with any authority figure, as the sneaking underling Iago attempts to overthrow his noble Captain. It is significant here, too, that (as many critics have pointed out) Iago has no real motive for his animosity. He does not articulate a critique, or even a complaint, about the way Othello exercises power. Instead, he simply says:

I hate the Moor

And it is thought abroad, that ‘twixt my sheets

He has done my office: I know not if’t be true;

But I, for mere suspicion in that kind,

Will do as if for surety.Rebellion against one’s superiors is presented as a matter of misguided jealousy and intrinsic spite. Similarly, the Puritan Malvolio in Twelfth Night, who aspires to the hand of a woman above him in social standing, is a hypocrite and a fool. The Puritan political resistance, or the Puritan ideological opposition to hierarchical norms, is never voiced, much less endorsed.

In Shakespeare, those in authority rarely provoke resistance through injustice. In general, the one thing Shakespeare’s rulers can do wrong is to shirk their authority, trying to retire too early (King Lear) or consorting with those beneath them (Henry IV.) Often, their role is to come on at the end as a kind of hierarch ex machina, assuring all that “Some shall be pardon’d and some punished,” like the Prince at the end of Romeo and Juliet, or Prince Fortinbras at the end ofHamlet (“with sorrow I embrace my fortune”—yeah, we bet you’re sorry).

It’s sometimes said that Shakespeare always wrapped things up with a king on his throne and all right with the world as a reflection of a general belief among his contemporaries in the Great Chain of Being—a conception of the universe as divinely ordered hierarchy, each subordinate in his or her divinely ordered place. But there were many people in Shakespeare’s time who were mistrustful of kings and received authority—real-life versions of Malvolio, who Shakespeare pillories. Within his own context and within his own milieu, Shakespeare consistently championed the most powerful, and set himself against those who challenged their authority. He saw hierarchy as good and rebels as evil.

None of this is a good reason to dismiss Shakespeare. But it is a good basis for critical skepticism toward him. What would Twelfth Night look like from Malvolio’s perspective—or even from a perspective where it is not on its face ridiculous to imagine someone marrying across class? What real grievances might Iago or Macbeth have if it were possible for Shakespeare to show us an authority figure who isn’t a paragon? What happens to Julius Caesar if the rebels have some actual, genuine concerns about tyranny? As Rosenberg says, Shakespeare was a man, not a god—and as a man, he had a particular perspective, particular axes to grind, and particular blind spots. His plays aren’t entombed, authoritative holy writ; they’re living arguments, which means that, at least at times, they’re worth rebelling against.

The second comes from The Washington Post, written by Alyssa Rosenberg and explores the notion that the way a play is adapted/staged/interpreted will, of course, have a bearing on its relevancy to a modern audience: What we get wrong when we talk about Shakespeare.

The fact that traditional techniques of puppet making and puppeteering are the centre of this effort is heartening, as is the use of traditional Malay instruments to play the soundtrack. Also, there is an alignment of characters with those in the traditional Wayang Kulit stories, which will hopefully widen the appeal. On the flip side, when the

The fact that traditional techniques of puppet making and puppeteering are the centre of this effort is heartening, as is the use of traditional Malay instruments to play the soundtrack. Also, there is an alignment of characters with those in the traditional Wayang Kulit stories, which will hopefully widen the appeal. On the flip side, when the  It has been a few months since I have written about the discussions and debate surrounding the streaming of theatre, live and recorded, to cinemas, performance venues and across the web. In my last two posts on the matter,

It has been a few months since I have written about the discussions and debate surrounding the streaming of theatre, live and recorded, to cinemas, performance venues and across the web. In my last two posts on the matter,

excellent insight to the Ramlila of Ramnagar and details the potential problems that face it in the 21st Century. The other, equally as informative, is by Saudamini Jain for the Hindustan Times, entitled

excellent insight to the Ramlila of Ramnagar and details the potential problems that face it in the 21st Century. The other, equally as informative, is by Saudamini Jain for the Hindustan Times, entitled