It’s that time of year again, where I am forced to confront my prejudices about the great British theatrical tradition of Pantomime. This year, the International Baccalaureate Organisation re-wrote their Theatre Arts course and Pantomime was placed firmly alongside other world theatre traditons such as the beautifully artistic Indian Kathakali and Japanese Noh. I’ve written about it before here (this time last year, in fact) and I still struggle with it as a legitimate theatre form. I can’t help finding it all rather crass.

I have to remind myself that every year in the UK (and some former British colonial territories) Pantomime is hugely popular – 23 professional performances in the London area alone. Add to these the hundreds of performances outside the capital and the thousands of amateur groups doing their festive Pantomime thing, it is the most popular theatre form in the UK. I’m not going to get into why it’s still so popular, and why it draws huge audiences – that fact is that it is, and it does. Take a look here at the National Database of Pantomime Performance to get a real sense of just how widespread the form is.

The golden age of pantomime

Panto has long provided the heart, soul and high camp of the festive season. How did it all begin?

As you get your kids and your parents and maybe your grandparents ready for your visit to the panto this year – and panto is still in rude health, for many people the only time in the year they go to a theatre – you might perhaps wonder how such a gloriously odd phenomenon came about. There are interesting reasons for this unique combination of the broadest of broad comedy, a sentimental love story, a hero in fishnets, a brick shithouse of a comedian in tights, a ton of spangly scenery and audience participation on a nearly terminal scale, but what’s most surprising is how passionately people have felt about pantomime throughout its history: it has been perceived as important, this mad farrago, this theatrical mongrel that is barely deserves the name of genre.

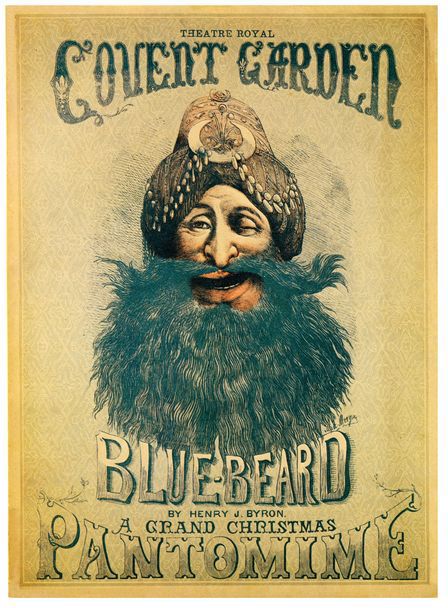

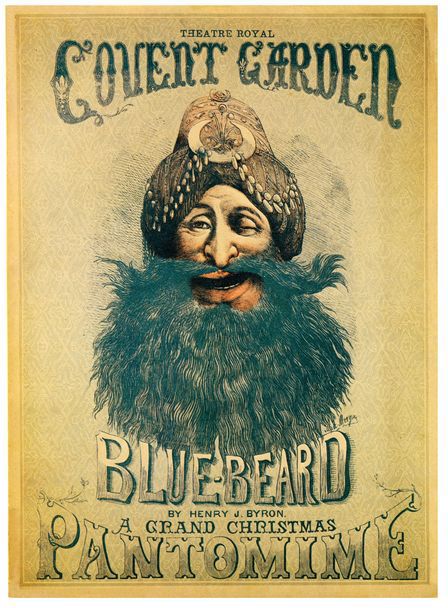

In 1867, the Era newspaper was pronouncing ex cathedra on the subject: “Time in his course has built up pantomime into an institution as venerable as Magna Carta, as sacred as the bill of rights, as dearly cherished as habeas corpus. The Pantomime is considered as worthy of the boards of Old Drury [Lane] as the works of Shakespeare himself.” But just five years later, there was a furious attack on the form pantomime was taking: what had happened to the charming clowns of yesteryear, the beauty, the innocence? What was this unrelenting emphasis on “that terrible managerial Frankenstein, the Transformation Scene”? No less personage than Ruskin wrote of the long-lost Arcadias of Pantomime. But the truth is that, like Christmas,, like Christmas, pantomime has never been what it was but was forever being refreshed and reinvigorated.

In a new book, The Golden Age of Pantomime, Jeffrey Richards opens with a brisk trot around the birth, development and – depending on your point of view – apotheosis or implosion of panto. It grew out of a partial and never entirely completed merger of three quite separate forms: the harlequinade, an almost completely wordless comic interlude, based on the classic commedia dell’arte characters of Arlecchino, Pantalone and Pulcinella; the extravaganza, a sophisticated and witty satire based on Greek and Roman myth or fairytales; and burlesque, which, as Richards says, irreverently sends up “everything the Victorians customarily took seriously: such as English history, grand opera and Shakespeare”. These elements sometimes existed separately, in parallel, as it were, and sometimes vied for dominance within pantomime itself. Inevitably, a form that was always essentially popular would also reflect the temper of the times, and those times were changing rapidly and radically.

Between 1780 and 1850, according to social historian Harold Perkins, “the English ceased to be one of the most aggressive, brutal, rowdy, outspoken, riotous, cruel and bloodthirsty nations in the world, and became one of the most inhibited, polite, orderly, tenderminded, prudish and hypocritical.” As with the nation, so with pantomime. The greatest of all British clowns, Joseph Grimaldi, who died in 1837, the year the young Victoria became queen, belonged to an older dispensation: Joey, “the urban Anarchist”, was a force of nature, “a half idiotic, crafty, shameless, incorrigible emblem of gross sensuality” ready, Richards says, “to defy authority, law and convention for his own immediate gratification”. His comedy was dangerous, reckless, but deeply recognisable; he was a Gillray cartoon come to life, embodying the spirit of the Regency.

But long before Grimaldi retired, the Evangelicals, seizing their moment as the industrial revolution wrought its changes, had moved in on the nation. And pantomime rapidly began to clean up its act. The genres of burlesque and extravaganza offered fantasies, either ancient or otherworldly, that transported the audience. They were not uncritical of the world around them – satire of a genteel order was acceptable – but the watchwords were elegance and taste. JR Planché, an homme de lettres of Huguenot stock, dedicated himself from his first play as early as 1818, to raising standards, to eliminating the “coarse exaggeration and buffoonery of pantomime”. Teaming up with Mme Vestris – deliciously described as “the most dangerous actress in London” – he wrote and produced a series of shows that were somewhere between extravaganzas and revues, often derived from the French theatre. Olympic Revels and its sequel Olympic Devils were major hits – Offenbach without the tunes. A costume historian by training, he introduced a new level of historical accuracy in setting and clothing and raised the visual tone.

He came to regret the prominence he had given to design. Victorians were intensely visually aware, fascinated by the vast array of new stimuli available to them – the illustrated magazines, the dioramas, the daguerreotypes, the museums – and above all intrigued by the power of optical illusion. A new generation of skilled scene-painters grew up to answer this fascination, and soon began to dominate the performances.

Dickens’s friend Clarkson Stanfield had painted many of the dioramas which were briefly inserted into the harlequinade; these proved so popular that they were expanded, and expanded, until, the element of spectacle that they provided threatened story, character, comedy. A master of painting and stagecraft then appeared, a man who has a reasonable claim to be considered the central genius of the Victorian pantomime – William Beverley, who year after year realised one astounding vision after another. It must have been like MTV for his audiences, a kind of theatrical Cinerama, though sometimes the descriptions make it sound more like an acid trip. In Riquet with the Tuft, the Times reported, “there are some 70 or 80 mushrooms, the chief fungus being Miss Hart, which, opening, gradually expand and disclose, reclining in each mushroom, a demon dressed in red with battle axe … when the mushrooms fully expand, the demons simultaneously rise, and beginning to dance, are interrupted by the appearance of Mother Shipton, when they fall to their knees, producing,” the reporter understates, “a novel and exciting effect”. After these transformation scenes had completed themselves, “Cries of Beverley! echoed instinctively though the house.”

Planché and his younger fellow author, EL Blanchard, both felt that their carefully crafted work was underappreciated. They were men of taste and intelligence and some sophistication; they summoned worlds that delighted their audiences. “Each Christmas and Easter for many years,” Richards writes, “the theatres for which Planché worked were filled with fairies, wizards, witches, ogres, dragons, elves, dwarves, sprites, anthropomorphic animals, spells and transformations, magic rings and magic swords, enchanted trees and flowers.” It was The Lord of the Rings avant la lettre. Blanchard, who left a remarkable diary that takes us right to the heart of the Victorian jobbing writer’s life, pulled off the enviable coup of reviewing his own shows under a pseudonym. “It is probably,” he wrote of one of his own pieces, “one of the most original in subject, and most effective in treatment that has ever been offered to the public in this or any other house.” Blanchard’s range was extraordinary, encompassing both fairytale whimsy and up to the minute topical comment, like The Birth of the Steam Engine or The World of Wonders; he was essentially conservative, but strongly against the 1872 Licensing Act: “Some folks have lately come to think / That other folks ne’er want to eat or drink / That bread and cheese and beer must lead to crime / Should they be swallowed past a certain time.”

Imperial themes increasingly began to feature in the shows, resulting in a carnival of political incorrectness: in Jack and the Beanstalk, played in the presence of the Prince of Wales, a group of minstrels – blacked up, needless to say – sang merrily in the background, as children dressed as monkeys swung from the trees, gaily dressed natives (also blacked up) flocked on with banners inscribed with the words “Tell mama we are happy”. In Queen Maba few years earlier, the Indian Mutiny was reenacted in comic form: at one point a clown, dressed in the uniform of the Grenadier guards, killed an insurgent sepoy, then stuffed his body into a mortar and fired him at a butcher’s shop, where he ends up on hooks, replacing the mutton and beef.

Cometh the hour, cometh the man: Augustus Harris Jr was himself an imperial figure: he took over Drury Lane, after two larger-than-life predecessors had failed, and made it a triumph of Roman proportions; Fleet Street dubbed him Augustus Druriolanus. At the same time as managing Drury Lane, he was running Covent Garden, Her Majesty’s and the Olympic, while sitting on the London County Council and serving as Sheriff of London for nine years. His day would start with dictation from the bath, after which he would meet his creative teams – there were always many shows going on simultaneously, each of which required his personal intervention. Writers, designers, costumiers did their best to keep up with him, executing his sometimes rather imprecise ideas, sketched out on tablecloths or scraps of paper. He met and dispatched the provincial managers, having quizzed them on the details, of which he always seemed to command a greater knowledge. He then proceeded to plough through an enormous lunch, which, his biographer said, ensured that on arrival at the theatre he would be filled with “an energy that was simply appalling”. He directed rehearsals intermittently, withdrawing to deal with some other aspect of the business; he would snatch a nap, or perhaps a more prolonged slumber, then change into evening dress. He stayed right to the end of every show, then dined extravagantly at his own restaurant before heading home to plan, scheme, dream the next cycle of work. Unsurprisingly, he died at the age of 46. His attitude was entirely pragmatic; he aimed to give the people what they wanted and the audiences loved what they got. It was often blatant jingoism. In 1897, the Kaiser was guyed as Prince Paragon. Two years earlier, in Jack and the Beanstalk, the giant was called Blunderboer. When he was arrested, from his pocket emerged a miniature army played by children, some riding small ponies, dressed as soldiers. “There was considerable enthusiasm,” says Richards, drily, “when they raised their helmets on their rifles and sang ‘Rule Britannia’.”

Not everyone was delighted. The spectacular element had gone way beyond anything that troubled Ruskin and co: “the monstrous glittering thing of pomp and humour,” said the Star in December, 1900, betraying an odd unease both with empire and this theatrical child of empire. But in another sense, Harris had restored panto to itself. He invited musical hall performers to participate in his shows, and with them, they brought something of the old rude energy, the quirkiness, the carnival quality that Grimaldi embodied. Genius actor-comedians such as Dan Leno and Marie Lloyd made an extraordinary impact, often writing their own lines and singing their own songs, with which the audience up in the gods gleefully sang along. Charles Lauri’s Man Friday was a vivid creation; Fred Storey’s King Hullaballoo played “with as much care and dramatic intensity as though he were playing King Lear – which of course,” the writer adds, “has been the method of the greatest burlesque actors”.

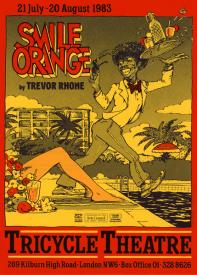

During the long twilight of empire, panto still rode high. Despite rationing, both of fabrics and building materials, it continued to triumph during and after the second world war. But the arrival of television at the end of the 1940s immediately threatened the existence of theatres and, more subversively, the nature of panto itself. TV stars who had little more than celebrity to offer were imported, while variety, from which panto had drawn so many of its stalwarts, was in sharp decline. It became simultaneously costly and vacuous and began to disappear from West End theatres; it survived elsewhere in Britain – not least in Scotland, where the variety tradition was, and is, still strong – but only just. Then, in the early 70s, something unexpected happened: shoots of new life started to emerge. Alternative panto began to flourish on the fringe: there were gay pantos, black pantos, feminist pantos and Marxist pantos, there were Chickenshed pantos, and physically challenged and able‑bodied young actors performed their Twankeys and their Abanazars, their Baron Hardups, their Dicks and their Jacks amid unseemly mirth.

And then another funny thing happened on the way to Christmas: a class of actors known derisively among the music hall community as lardies – legitimate actors – became interested in what they would no doubt have called “the genre”: the RSC presented a panto in 1981; and Ian McKellen and Roger Allam gave the spirit of Lilian Baylis a spin in 2004 when they triumphantly brought Aladdin in all its ribaldry to the Old Vic. Meanwhile, a generation of American stars who had – who knew? – theatre backgrounds showed up to give their Captain Hooks, with actors like David Hasselhoff and Henry Winkler performing alongside copper-bottomed (no, missus!) homegrown stars such as Christopher Biggins and Bonnie Langford, who carry the grand old traditions forward like beacons.

There has always been a certain uncertainty about what panto is – which continues to the present day. Above all, it’s about the relationship between the actors and the audience. It is essentially theatrical. It can be magical and it can be hilarious; it can be awe-inspiring and it can be seriously subversive. As long as it’s alive and kicking, it’s in touch with its roots.

It strikes me that Pantomime has a long and subversive history, which has been generally lost in its current, Z list celebrity filled form. Shame!

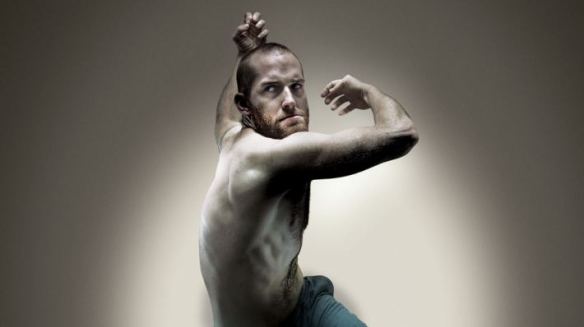

I am often asked where I draw my ideas and sources from for Theatre Room. Today’s post is a good example of just how eclectic and diverse those inspirations often are. The image on the left first popped up in my Facebook feed, but it was a busy day and I didn’t read the accompanying post. A day or so later I saw the same photograph in a picture gallery in The Telegraph of a performance celebrating Twelfth Night in London. So this is where the trail began. The photograph is in fact of an old friend of mine, Daniel, who is trustee of and occasional performer with a company called The Lions Part. The Lions Part, amongst other things, recreate traditional Mummers Plays, one of the oldest theatrical traditions in Europe. Mummers Plays or Mumming are short dramas with rhyming texts, traditionally performed at certain times of the year, usually associated with traditional Christian or Pagan festivals, such as Christmas or All Hallows Eve (Halloween). The origins of Mumming are a little obscure, but have been traced to medieval Europe, most specifically Germany, Britain and Ireland although there are suggestions that it was much older than that, perhaps even stretching as far back as ancient Egypt. Another theory places the emergence of Mumming alongside that of Pantomime in the 1700’s, with connections therefore, to Commedia dell’arté

I am often asked where I draw my ideas and sources from for Theatre Room. Today’s post is a good example of just how eclectic and diverse those inspirations often are. The image on the left first popped up in my Facebook feed, but it was a busy day and I didn’t read the accompanying post. A day or so later I saw the same photograph in a picture gallery in The Telegraph of a performance celebrating Twelfth Night in London. So this is where the trail began. The photograph is in fact of an old friend of mine, Daniel, who is trustee of and occasional performer with a company called The Lions Part. The Lions Part, amongst other things, recreate traditional Mummers Plays, one of the oldest theatrical traditions in Europe. Mummers Plays or Mumming are short dramas with rhyming texts, traditionally performed at certain times of the year, usually associated with traditional Christian or Pagan festivals, such as Christmas or All Hallows Eve (Halloween). The origins of Mumming are a little obscure, but have been traced to medieval Europe, most specifically Germany, Britain and Ireland although there are suggestions that it was much older than that, perhaps even stretching as far back as ancient Egypt. Another theory places the emergence of Mumming alongside that of Pantomime in the 1700’s, with connections therefore, to Commedia dell’arté

The latest piece from internationally renowned physical theatre company

The latest piece from internationally renowned physical theatre company